The Largest Wooden Ship Graveyard in the Western Hemisphere

The Mallows Bay-Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary is home to one of the largest and most varied collections of maritime heritage resources in the United States, representing over three centuries of American history, from the Revolutionary War era to the present. To date, there are 141 known shipwrecks within the 18 square mile sanctuary with the possibility of discovering new wrecks as further surveys are conducted. In April 2015, the National Park Service recognized the area's national significance by designating it as the Mallows Bay-Widewater Historic and Archaeological District.

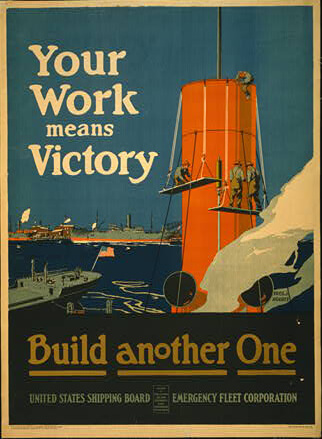

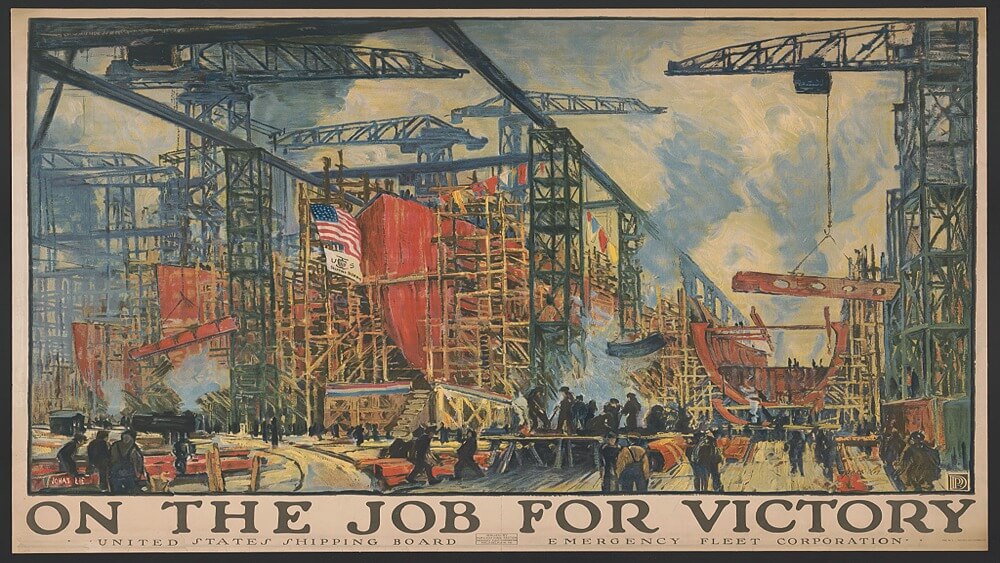

Mallows Bay has the distinction of being the largest wooden ship graveyard in the Western Hemisphere, with the remains of over 100 wooden steamships and many other vessels resting in the bottom sediments of the bay. Most of these ships, known as the "Ghost Fleet," were built for the U.S. Emergency Fleet between 1917 and 1919 as part of America's involvement in World War I. Their construction took place in at least 189 shipyards across 26 states, reflecting a massive wartime effort that drove the expansion and economic development of communities and related maritime services. Although nearly 300 ships were constructed, the war ended before the fleet was completed. While some ships carried cargo to Hawai‘i and other destinations, none reached the theater of war.

Historical Background

Shipbuilding during World War I led to the formalization of the U.S. Merchant Marine. Although merchant mariners already existed in the United States, the construction, operation, and maintenance of hundreds of new vessels significantly increased the need for skilled mariners. This rapid need for ships and trained crews during the war resulted in the development of the infrastructure that pushed America to the forefront of shipbuilding and global trade in the 20th century.

Although nearly 300 wooden ships were built, the war ended before they could be utilized. Many of these ships were scuttled in the Potomac River to salvage their scrap metal, such as engines, steam boilers, and propellers. They became known as the Ghost Fleet and underwent three separate shipbreaking and metal salvage periods from the 1920s through the 1940s.

Most of the ships were purchased by the Western Marine and Salvage Corporation and kept in the Potomac River near Mallows Bay. A few at a time were taken to Alexandria, Virginia, where they were dismantled for scrap metal. The remaining ships in the Potomac occasionally caught fire or broke loose, becoming hazards to navigation. As a result, the company was ordered to secure them. To comply, they burnt many of the ships to the waterline before floating them into Mallows Bay.

During the Great Depression, Western Marine and Salvage Company went bankrupt, which allowed local communities on both sides of the river to salvage the ships’ remains for needed income. At the start of World War II, Baltimore's Bethlehem Steel initiated the third and final shipbreaking period, which lasted only two years.

Ships as Valuable Habitats

Today, over 100 of these World War I-era ships remain in the sanctuary, and after more than a century, natural processes have gradually transformed them into ecologically valuable habitats. The overgrown wrecks now form a series of distinctive islands, intertidal habitats, and underwater structures that are critical to fish, beavers, and birds such as ospreys, blue herons, and bald eagles. Although the sanctuary does not manage or regulate these natural resources, the unique blend of history and ecology attracts and captivates visitors.

The Shipwrecks

Accomac

Starboard view of Accomac, with one osprey nest at the bow, and another at the stern. (Photo: Will Sassorossi/NOAA).

Afrania

Close up of Afrania with remains outlined in red. (Source: Duke University/NOAA).

Aowa

Remains of Aowa, stern in the foreground with the bow facing toward the Maryland shoreline. (Photo: Matt McIntosh/NOAA).

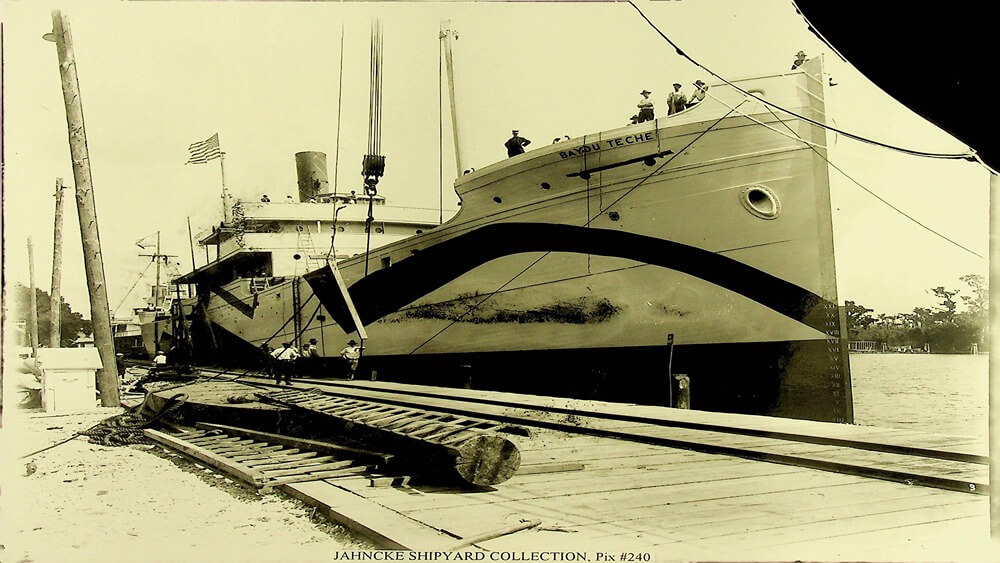

Bayou Teche

View of starboard side of Bayou Teche at Jahncke Shipyard, displaying dazzle painting, date unknown. (Source: Courtesy of Southeastern Louisiana University, Center for Southeast Louisiana Studies, Jahncke Shipyard Collection).

Benzonia

Close up of Benzonia, as part of a larger image mosaic that utilized drones. (Source: Duke University/NOAA).

Boone

The remains of Boone (centered of image), located within Mallows Bay-Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary. (Source: Duke University/NOAA).

Dertona

Moosabee and Dertona, two of the "Three Sisters" wrecks (lower left hand corner of the image), located in Mallows Bay-Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary. (Photo: Tyler Smith/NOAA).

Mono

"On The Job For Victory" poster showing a panoramic view of a busy shipyard, 1917, by United States Shipping Board Emergency Fleet Corporation. (Source: Library of Congress).

Moosabee

Aerial drone photographic mosaic of "Three Sisters" wrecks, located within Mallows Bay-Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary. (Source: Duke University/NOAA).

Namecki

Vessel Namecki displaying dazzle paint (camouflage), 1918. Dazzle paint was used in an effort to confuse the enemy by attempting to disguise the speed and heading (direction) of the vessel. (Source: Courtesy of the Fleet Library at Rhode Island School of Design, Special Collections).

Yawah

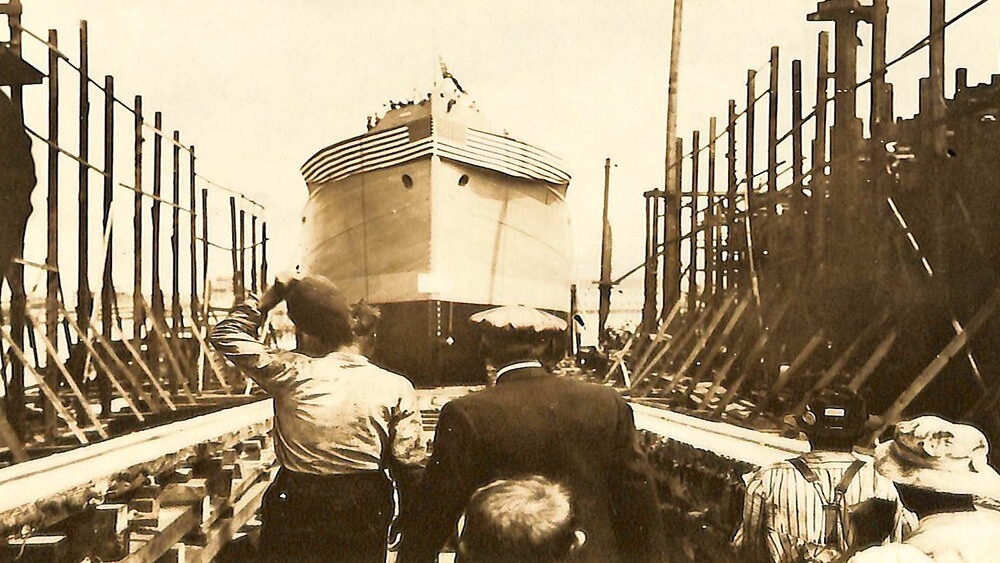

Launching of Contoocook (later named Yawah) at the Shattuck shipyard, Newington, NH, November 7, 1918. (Source: In memory of L. H. Shattuck and his daughter Althea, courtesy of the Portsmouth Athenaeum).