January 2025

NOAA has announced its decision to designate Papahānaumokuākea National Marine Sanctuary, a 582,570 square-mile area in the Pacific Ocean that is two times the size of Texas. The sanctuary is within the existing Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, and provides additional protections and management tools to strengthen conservation of the marine areas of the monument.

Papahānaumokuākea National Marine Sanctuary is one of the largest marine conservation areas in the world. NOAA will co-manage the sanctuary with the state of Hawaiʻi and in partnership with the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, consistent with the pre-existing management of the marine national monument.

“The waters that surround the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are undeniably unique and incredibly important culturally, economically, ecologically,” said John Armor, the director of NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. “Today’s action will help ensure that the coordinated management and robust conservation efforts of NOAA and its partners persists for generations to come.”

Papahānaumokuākea benefits significantly from its designation as a national marine sanctuary under the National Marine Sanctuaries Act, which provides a strong legal framework for its conservation and protection. This law allows the secretary of commerce to manage and protect marine areas designated for their ecological, cultural, or historical significance, and helps limit activities that could harm the marine environment, such as destructive fishing practices and certain types of industrial development. In addition to these protections, the sanctuary status facilitates scientific research, resource monitoring, and coordinated efforts to ensure the long-term health of this unique and ecologically rich area.

Papahānaumokuākea will still maintain its status as a marine national monument and a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The Piko (Origin) of Hawaiian Culture

Papahānaumokuākea holds deep cultural importance for Kānaka ʻŌiwi (Native Hawaiians), who view it as a sacred place where all life begins and a place where ancestral spirits return after death. Hawaiian oral traditions, like the Kumulipo creation chant, describe the emergence of life from "Pō" (a primordial darkness) within Papahānaumokuākea, signifying its role as the source of all creation. The name Papahānaumokuākea honors the Hawaiian deities Papahānaumoku (Earth mother) and Wākea (sky father), whose union is said to have created the Hawaiian islands. As such, the area is essential for Native Hawaiian cultural practices and maintaining a connection to ancestors.

Ancestors of Native Hawaiians today settled in the Hawaiian Archipelago likely between 1000 and 1200 AD and trace their ancestry to the Marquesas Islands and Tahiti. Once these settlers arrived in Hawaiʻi, the land, elements and wildlife shaped their culture and way of life. The Hawaiian Archipelago stretches in a northwest direction, starting from the Moku o Keawe (Hawaiʻi Island) at the southern tip, all the way up to Holanikū (Kure Atoll) in Papahānaumokuākea, a distance of more than 2,400 kilometers (1,500 miles).

Hawaiians are part of a larger group of native Pacific Islanders, called Polynesians, a term meaning “many islands” in Greek. Polynesians have a long history of open ocean navigation using the art of wayfinding and celestial navigation. Polynesia is defined as a vast triangle with Hawaiʻi forming the northern point and Aotearoa (New Zealand), and Rapa Nui (Easter Island) forming the base of the triangle. The islands of Polynesia were the last islands settled in the Pacific (affectionately referred to as Moananuiākea) and represent one of the greatest feats of settlement and exploration.

The islands have many wahi pana (sacred sites) where Pacific Islanders, including Native Hawaiians, practice cultural rituals and ceremonies, reaffirming their connections with plants, birds, marine life, and place. Celebrating the interconnectedness of all life with place is a cornerstone of Native Hawaiian culture.

Haunani Kane, assistant professor at the School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology at University of Hawaiʻi Mānoa and research representative on the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve Advisory Council explains this significance from her own experience and perspective: “Papahānaumokuākea is a school for voyagers. One of the first navigation challenges or tests for young Hawaiian navigators is to leave the high islands of Hawaiʻi and find Nihoa. You are challenged with an open ocean crossing, and as you approach the island you are greeted by the birds telling you land is close. Seeing the peaks and cliffs of Nihoa emerge over the horizon at dawn is something we will all remember forever.”

A Biodiversity Hotspot

This expansive area of coral reefs, seamounts, banks, and shoals is home to a wide variety of invertebrates, fish, birds, marine mammals, and other wildlife, many of which are found only in the Hawaiian Islands (endemic species).

The orange margin butterflyfish (Prognathodes basabei) was first seen from submersibles at depths of up to 600 feet in the main Hawaiian Islands, but researchers were unable to collect any specimens. In 2017, NOAA technical divers collected specimens at Manawai in Papahānaumokuākea at a depth of 200 feet. A genetic analysis of tissue samples showed this was a new species, distinct from similar butterflyfishes and endemic to Hawaiʻi. Photo: Greg McFall/NOAA

The deep reef alga Croisettea kalaukapuae was discovered in 2022 and named after Laura Kalaukapu Thompson, long-time advisory council member, mother of traditional navigator Nainoa Thompson, and life-long advocate for conservation. The alga is endemic to deep reefs of Papahānaumokuākea. Photo: Cameron Ogden-Fung/NOAA

Due to their evolutionary isolation, endemic species are particularly vulnerable to disturbances from changing ocean conditions and the introduction of invasive species. Scientists have identified reefs within the waters of Papahānaumokuākea that contain the highest concentrations of endemic species found anywhere on the planet. Research teams have used advanced dive gear to explore undocumented mesophotic, or “middle-light”, ecosystems down to 330 feet, discovering new marine plants and animals, and uncrewed systems are being used to explore and reveal habitats miles below the surface where life thrives in darkness and extreme conditions. The 2024 NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer expedition to Papahānaumokuākea served to increase mapping coverage in unexplored areas with a focus on waters deeper than 200 meters (656 feet).

“Because many of these species are specifically adapted to their environment, their loss can disrupt the entire food web and ecosystem functions,” says Randy Kosaki, research ecologist at Papahānaumokuākea National Marine Sanctuary. “The presence of many endemic species helps maintain ecosystem stability and biodiversity, which are key components of resilience. We are learning how marine habitats can recover from human impacts and how large-scale conservation efforts can better support these ecosystems.”

The waters of Papahānaumokuākea are also crucial habitats for threatened and endangered species. In 2007, breeding and calving activity of koholā (humpback whales) was documented for the first time in Papahānaumokuākea. In 2020, the Wave Glider, a remotely operated surface vehicle equipped with sound recorders, traveled 2,600 miles over 67 days, recording the presence of koholā throughout the sanctuary. The shallow waters of the sanctuary are also crucial habitats for rare species like the threatened honu (green sea turtle) and the endangered ʻīlioholoikauaua (Hawaiian monk seal).

Papahānaumokuākea is the most important habitat for in situ conservation of a number of endangered species. ʻĪlioholoikauaua (Hawaiian monk seals) are found only in Hawai‘i, with the main breeding subpopulations located throughout the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and a small but growing population in the main Hawaiian Islands. Photo: Photo: Koa Matsuoka/USFWS

Continuing to protect and study the marine life and habitats in the 582,570 square-mile Papahānaumokuākea National Marine Sanctuary is crucial to conserving marine biodiversity throughout Hawaiʻi—and to preserving the Native Hawaiian culture and economies that rely on this thriving marine ecosystem.

A Sanctuary At Last

Decades of work by several agencies and individuals has led to increasing levels of protection for Papahānaumokuākea. The area has a long history of being considered for national marine sanctuary designation.

-

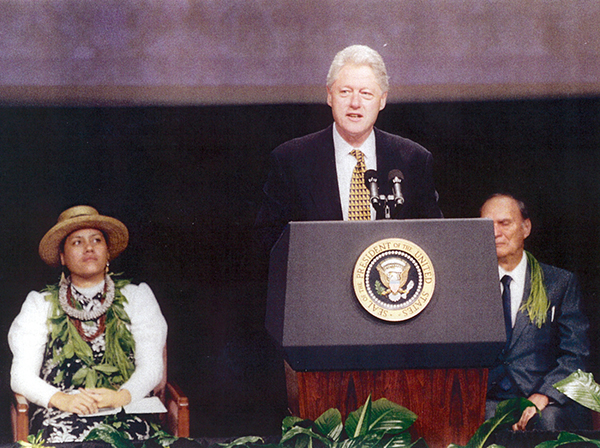

2000

President William J. Clinton created the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve by executive order, which directed the secretary of Commerce to designate the reserve as a national marine sanctuary.

Photo: NOAA

-

2006

President George W. Bush designated Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument by proclamation based in part on the sanctuary designation process that was already underway and near completion.

Photo: Official White House Photo by Eric Draper, 2006

-

-

2016

President Barack H. Obama followed the original monument designation with a proclamation, designating the Monument Expansion Area to the full extent of the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone. The proclamation directed the secretary of commerce to consider designating Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument and the Monument Expansion Area as a national marine sanctuary.

Photo: Official White House photo by Pete Souza

-

2021

The Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 directed NOAA to initiate the sanctuary designation process (see next section for details).

Stakeholder groups and partners, including the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve Advisory Council and the state of Hawaiʻi, have also supported the process to designate the area as a sanctuary. The state of Hawaiʻi co-developed the draft and final environmental impact statements and will co-manage the sanctuary.

When asked about the significance of this milestone, Dawn Chang, chairperson for the Board of Land and Natural Resources said, "The inclusion of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine Refuge in the newly designated Papahānaumokuākea National Marine Sanctuary ensures long-term protection for an area that hosts unique and limited natural, cultural, and historic resources, which the state of Hawaiʻi’s Department of Land and Natural Resources holds in public trust for future generations of Hawaiʻi. The department looks forward to continuing co-management of this marine area with NOAA and continuing co-management of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument with the monument co-trustees."

He inoa no Papahānaumokuākea: A Name in Reverence of Papahānaumokuākea

Papahānaumokuākea is a place of extraordinary beauty, known by a single name but recognized through many esteemed designations.

Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument's designation in 2006 not only had a significant impact on the protection of Hawaiʻi’s marine ecosystems, but also helped inspire a global shift toward the creation of large-scale marine protected areas. The success and recognition of Papahānaumokuākea demonstrated the importance of protecting vast, ecologically critical marine environments, and this led to the establishment of several similar large marine protected areas around the world.

One of the key outcomes of Papahānaumokuākea's Marine National Monument’s creation was the development of Big Ocean, a global network designed for the exchange of knowledge and best practices in the management of large-scale marine protected areas. Big Ocean is the only peer-learning network specifically created ‘by managers for managers,’ meaning it is led by those who directly oversee and manage large marine protected areas.

Papahānaumokuākea provides refuge for endangered species such as this honu (Chelonia mydas) at Manawai (Pearl and Hermes Atoll). Photo: John Burns/NOAA

Papahānaumokuākea's latest designation as a national marine sanctuary under the National Marine Sanctuaries Act further strengthens its legal protections and management capabilities.

“This designation elevates the site to a higher level of conservation, joining a network of 17 existing national marine sanctuaries across the country and ensuring that it benefits from a comprehensive framework that is aligned with best practices in cultural stewardship, marine science, and resource protection,” Papahānaumokuākea National Marine Sanctuary Superintendent Eric Roberts clarifies.

In the spring, the new sanctuary will work to transition the existing Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve Advisory Council into a Sanctuary Advisory Council. These advisory councils are an important provision within the National Marine Sanctuaries Act and play a vital role advising sanctuary staff and NOAA on sanctuary operations, including education and outreach, research and science, cultural considerations, regulations and enforcement, and management planning. Council members also play an important role as liaisons between their constituents in the community and sanctuary leadership.

Those interested in helping to shape the future of Papahānaumokuākea National Marine Sanctuary can subscribe to the sanctuary’s listserv for future updates on advisory council membership and recruitment. To learn more about the difference between marine national monuments and national marine sanctuaries, take a look at some resources on the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries website.

More Information

- NOAA Press Release Announcing New Sanctuary

- Papahānaumokuākea National Marine Sanctuary Website

- Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument Website

- Papahānaumokuākea UNESCO World Heritage Site

Rachel Plunkett is the content manager and senior writer/editor at NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries