NOAA launches Mission: Iconic Reefs to save Florida Keys coral reefs

By Elizabeth Weinberg

December 2019

The coral reefs at the foot of Florida are legendary, making up a barrier reef that spans more than 255 continuous miles. The reefs are home to lobster, sea turtles, fish, and more, and they have protected the coastline from storm surge for thousands of years. But these coral reefs, like coral reefs across the globe, are in serious trouble.

In recent decades, the coral reefs within Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary have been damaged by hurricanes, bleaching, disease, and heavy human use. The sanctuary and its partners are working diligently to protect the reefs, but our efforts have not been able to keep up with the decline. Now, NOAA and our partners are launching Restoring Seven Iconic Reefs: A Mission to Recover the Coral Reefs of the Florida Keys, one of the largest investments in reef restoration anywhere in the world. By restoring corals at seven iconic reef sites in Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, we can change the trajectory of an entire ecosystem and help save one of the world’s most unique areas for future generations.

Why restore?

Photo: XL Catlin Seaview Survey/The Ocean Agency

More than 6,000 species of plants and animals call the Keys home, and many are found on the coral reefs. Recreationally and commercially important fish species shelter and feed on the reefs, as do spiny lobster, sea turtles, and more.

In addition to supporting diverse animal and plant life, the coral reefs of the Keys are important for the survival of human communities throughout this island chain. Structurally, the corals create a barrier between the islands and the open ocean, dissipating wave energy and diminishing the impacts of storms and high tides. And they also form the basis of the Florida Keys economy: 5 million people visit each year – most of whom participate in ocean recreation and enjoy the reefs – contributing $2.4 billion in sales annually. Here, more than one out of every two jobs is connected to the marine ecosystem

But in the last 40 years, healthy coral cover in the Florida Keys reefs has declined more than 90 percent. This decline can’t be blamed on a single cause, but rather a web of interconnected problems. Misplaced boat anchors and ship groundings crush healthy reefs. Pollution makes it difficult for corals to survive, while overfishing damages the fish populations that are necessary to maintain reef health. Storms like 2017’s Hurricane Irma can rip corals from their foundations and smother those that remain with sediment. In recent years, afflictions like stony coral tissue loss disease have killed off huge percentages of once-healthy coral. And if all this wasn’t enough, the coral reefs of the Florida Keys also must contend with climate change: elevated ocean temperatures cause bleaching in corals, which can compromise their health or even kill them.

Without our help, the corals will no longer be able to provide the structure, habitat, and beauty for which the Florida Keys are known. The ecosystem will change – indeed, it is already changing – to algae-dominated habitat. In addition to no longer providing storm protection, the fallen reefs will force a shift in the economy of the Florida Keys, fundamentally changing the local culture.

“The once iconic coral reefs of the Florida Keys have suffered dramatic declines over the last 40 years and now straddle a tipping point," says Dr. Neil Jacobs, acting NOAA administrator. “Quick and decisive action has the very real potential to turn this decline around before it’s too late.”

Seven iconic reefs

Photo: Coral Restoration Foundation

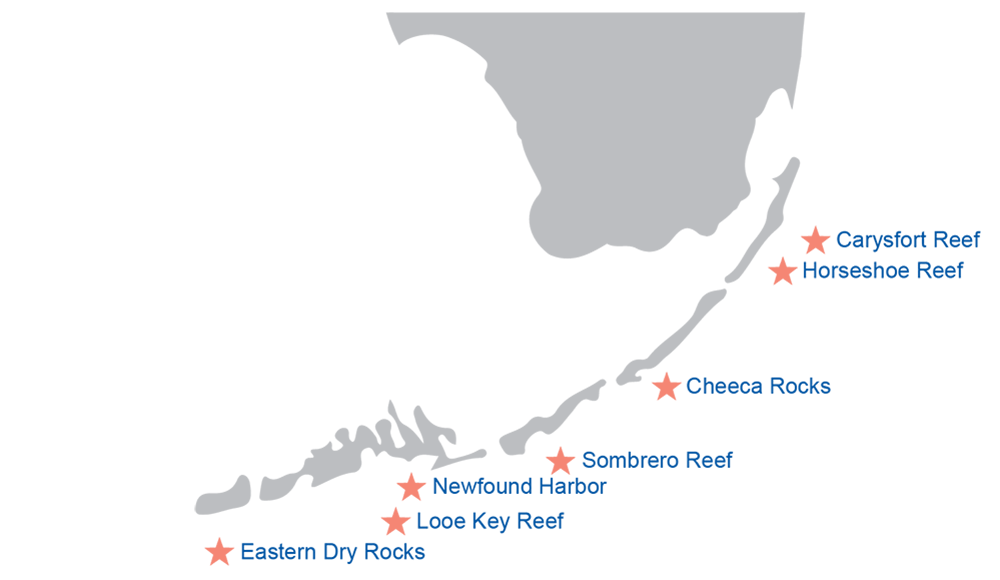

“Losing the reef is not an option, but that’s what could happen without action,” says Tom Moore, leader of NOAA’s Coral Reef Restoration Team. This April, NOAA gathered a group of more than 25 researchers, restoration practitioners, and members of state and federal agencies. Together, these experts created a first-of-its-kind restoration strategy that will focus on seven distinct coral reefs within the Keys.

The sites – Carysfort Reef, Horseshoe Reef, Cheeca Rocks, Sombrero Reef, Newfound Harbor, Looe Key Reef, and Eastern Dry Rocks – span the full geographic range of the region, a variety of habitats, and a diversity of human uses. Most crucially, these sites all either have a history of restoration success, or have characteristics that suggest restoration is likely to succeed.

Access regulations to these areas will not change, and the public will still be able to visit these reefs. However, during active restoration, we may temporarily reduce access to allow for the work to be completed efficiently and safely.

This NOAA-led effort is supported by partners at the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commision, Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Coral Restoration Foundation, Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium, Florida Aquarium, The Nature Conservancy, Reef Renewal, and the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation.

How the restoration works

Photo: David J. Ruck/NOAA

Corals grow slowly, and this coral restoration project will take time. Mission: Iconic Reefs uses several phases to ensure that multiple coral species and other important reef species can be restored over time.

First, we will remove nuisance and invasive species like algae and Palythoa, an invertebrate that grows in thick mats. These species compete with corals for space on the reef and prevent coral larvae from settling and growing. Removing them will let the growing corals avoid expending energy competing for reef space.

Then, Phase 1 of the plan begins. Over the first seven to 10 years of this effort, we and our partners will outplant a variety of coral species. Elkhorn corals will be outplanted first: these corals grow relatively quickly and are not susceptible to stony coral tissue loss disease. As soon as they are planted, the elkhorn corals will create habitat for other animals, and within three to five years, they will reach reproductive maturity and be able to help grow the reef.

As the elkhorn corals take hold, other species will be outplanted, including star, brain, pillar, and staghorn corals. We intend to supplement the reefs with sea urchins and Caribbean king crab, which eat algae that can overgrow coral reefs. Over this first phase, we aim to increase the coral cover across these seven sites from two percent (the current assessed coral cover based on 2019 observations of Iconic Reef sites) to 15 percent depending on the particular habitat zone. Coral cover is a measure of the proportion of reef surface covered by live stony coral, the primary contributors to coral reef ecosystem health. A healthy coral reef may have between 25 and 40 percent coral cover, with stony corals mixed in with sponges, soft corals, algae, and other organisms.

Phase 2 of the plan builds on this restoration. Over approximately 12 years, restoration volunteers and staff will continue to outplant elkhorn, star, brain, pillar, and staghorn corals. They will also outplant other small stony corals like finger and brain coral, helping to add diversity, function, and resiliency to the reef. By the end of this phase, we aim to increase coral cover to an average of 25 percent.

Throughout the entire restoration effort, a workforce of professional and volunteer divers will serve as “gardeners” on these reefs. They will remove marine debris, nuisance species, and species that might compete for space, and also reattach any corals that have been damaged or disconnected.

“Ten years ago, this project would be just a wild dream,” says Ken Nedimyer, Reef Renewal founder. But now, “we’re at a place in time where we have the technology to undertake a project of this size and we have a window of opportunity to do so. Not only can we think about doing it, but the need to do it is overwhelming.”

Coral nurseries

Photo: XL Catlin Seaview Survey/The Ocean Agency

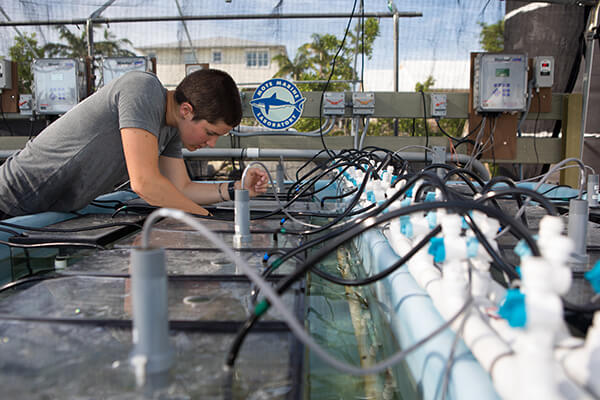

Mission: Iconic Reefs, unparalleled in scope and scale, will require nearly 500,000 stony coral colonies. That number of corals is a huge lift, but by working together, multiple partners are up to the task.

Some partners, including Reef Renewal, Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium, and Coral Restoration Foundation, will raise the quick-growing, Phase 1 corals in nurseries in the ocean. Mote and The Florida Aquarium will augment these farms with corals grown in laboratories: these will be slower-growing corals, corals screened for resilience, and corals bred to increase genetic diversity.

“We have been working on scaling up our restoration efforts,” says Scott Winters, CEO of Coral Restoration Foundation. “But if we want to save the Florida Reef Tract, we can be more effective if we work together. We have an opportunity to combine our expertise to have a hugely significant impact on the future of our coral reefs.”

“We are excited that Mote’s science-based coral restoration initiative will be a major component in the plan,” echoes Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium President and CEO Dr. Michael P. Crosby. “This is an unprecedented effort to respond to an unprecedented environmental emergency. Together with our partners, I am convinced we will be able to save Florida’s coral reefs.”

The Nature Conservancy, SECORE, University of Florida, University of Miami, and Nova Southeastern University will also lend scientific expertise. NOAA’s Restoration Center and the NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program have awarded $5.3 million in grants for restoration over the next three years. Subsequently, the plan will be funded through many public and private funding streams, coordinated by the new Florida Keys Restoration Council.

Corals for the community

Photo: Daryl Duda

“The reefs are home to this community. They are part of our way of life,” says Sarah Fangman, Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary superintendent. “We want to give people the chance to be part of healing the Keys, and we need the community’s support to make this vision a reality.”

Volunteers can assist with invasive species removal and long-term nursery and reef maintenance. Blue Star operators will be key to the continued recovery of the Florida Keys reef tract, as they are committed to responsible tourism, diving, and fishing. Mission: Iconic Reefs will also foster a new economic sector for the Florida Keys region centered around this innovative effort.

“We hope the Mission: Iconic Reefs effort can be beneficial not just in the Florida Keys,” adds Fangman, “but also in other reefs around the world. We hope we can give back and pay it forward.” Coral reefs all over the world are stressed by human use, climate change, and other global stressors. Mission: Iconic Reefs serves as a model for all these coral communities. By working together and supporting these iconic reefs, we can all create a lasting legacy and a physical and financial safety net for the Florida Keys, and help support coral restoration efforts worldwide.

Elizabeth Weinberg is the digital outreach coordinator and writer for NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries.