May 2023

Lighthouses have been part of our maritime cultural landscapes for millennia. One of the seven ancient wonders of the world was the Pharos, or Lighthouse, of Alexandria which was built more than 2,000 years ago and stood over 300 feet tall. The first lighthouse in the U.S., a maritime country of long shorelines and vast lakes and seas, wasn't quite that old, being built in 1716 in Boston. According to the National Archives, there were about a dozen lighthouses in existence when the federal government took over their design, operation, and maintenance in 1789 under the U.S. Lighthouse Establishment. The Establishment was replaced in 1852 by the U.S. Lighthouse Board, which in turn was replaced by the U.S. Lighthouse Service in 1910. In 1939 the Lighthouse Service was folded into the U.S. Coast Guard.

Lighthouses, and those who kept them, have often been cast with a romantic, brooding loneliness. But keeping lighthouses was hard, isolated, dirty, sometimes dangerous work, and one that often included the families of the keeper. In many cases, the wives, sisters, and daughters of male keepers took over the responsibilities of keeping the life-saving lighthouses functional if their relatives fell ill or died. Many of these women were appointed in their own capacity afterward, which also protected the family from falling into poverty since in the 19th century, society left women with little recourse for economic support except from their husbands or other family. This didn't change the fact that these women were strong, capable, and dedicated, and, as we'll see, rather extraordinary. Come meet some of these historic female keepers of lighthouses in and near national marine sanctuaries, starting in the Great Lakes.

Elizabeth Whitney Williams, Beaver Island Harbor Lighthouse and Little Traverse Lighthouse, Lake Michigan, Michigan

Two lighthouses just north of Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary were a central focus of the adult life of Elizabeth Whitney Williams. Elizabeth's first husband Clement Van Riper became the lighthouse keeper at the Beaver Island Lighthouse in 1869, and by 1870, with him in poor health, she took charge of the keeping the light. Tragedy struck in 1872 when Clement rowed out on a stormy night to help a ship in distress and never returned home. She wrote in her autobiography "A Child of the Sea and Life Among the Mormons" of her sorrow but also of the comfort that staying at the lighthouse would give her, and she was made lighthouse keeper in that same year.

Elizabeth remarried, to Daniel Williams, in 1875 and unlike most other women keepers who did so, she kept her position. In 1884 she requested a transfer to the new lighthouse that had just been completed in Little Traverse and remained there as keeper until 1913, when she and Daniel retired to Charlevoix, Michigan. She ends her autobiography beside the water, writing: "The sun has sunk in the west, leaving the sky all purple and pink. The moon, just risen, sheds her soft, mellow light over the earth; all nature is resting. The birds are in their nests, the whip-poor-will has ceased her plaintive notes, the sea gulls are soaring away to their nightly rest. No sound is heard save the soft, low murmurings of the waves upon the shore."

Anna Garrity, Presque Isle Lighthouse, Lake Huron, Michigan

Anna Garrity was born into the lighthouse keeping business. Her father was the keeper of the Old Presque Isle Lighthouse from 1861 to 1871, which overlooked what is now Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary, before moving a few miles to take over the newly complete New Presque Isle Lighthouse. Anna was born there in 1872, the youngest of seven children, and Anna and her siblings grew up learning how to tend the light. Her three brothers all worked as lighthouse keepers and both she and her mother Mary served as assistant lighthouse keepers with her father and brothers for years. Anna became head lighthouse keeper herself at the Presque Isle Harbor Range Light in 1903. Through personal injury, multiple forest fires, and tough, isolated conditions, she faithfully kept the light until 1926, when she retired to Alpena.

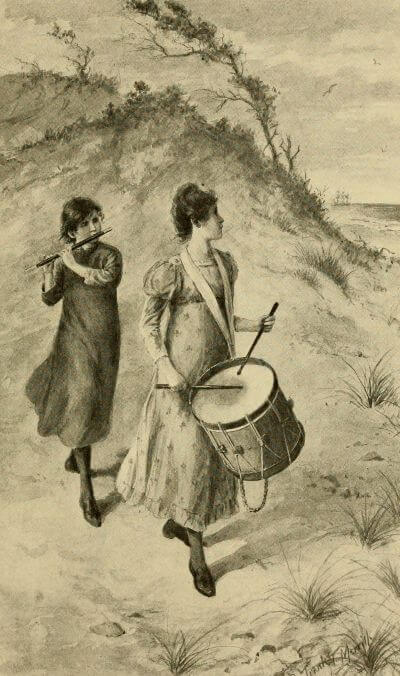

Rebecca and Abigail Bates, Scituate, Massachusetts

Rebecca and Abigail Bates were the daughters of lighthouse keeper Simeon Bates in Scituate, Massachusetts (today the location of the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary offices). During the War of 1812, Rebecca, 21, and Abigail, 17, were alone near the lighthouse when a British warship launched boats filled with soldiers who were going to attack the unsuspecting town. Without time to warn the residents, Rebecca and Abigail grabbed a fife and drum from the lighthouse and played as loud as they could. The British soldiers assumed that the Scituate militia was on to them and returned to the warship, retreating in haste. This event earned the two women the nickname "The American Army of Two".

Venus Parker, Killick Shoal Light, Virginia

The Chesapeake Bay region, home to Mallows Bay-Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary, yields another story of a female lighthouse keeper. Venus Parker, wife of lighthouse keeper William Major Parker (believed to be the first Black person named a lighthouse keeper in the U.S. and one who faced racism and physical harm for doing his job), is one of the few Black women we know of who kept lighthouses. She was born in 1862 in Virginia to free parents James and Elizabeth Nedab, married William in 1880, and was the mother of two. From 1886 until 1911, William served as the keeper of Killick Shoal Lighthouse, offshore of Accomack County, Virginia. In her book "Images of America: Assateague Island" (2011), Myrna J. Cherrix records remembrances of "Aunt" Venus waving to ferry passengers as they chugged past the lighthouse. According to the Chesapeake Chapter of the U.S. Lighthouse Society, when William died in 1912, Venus took over the responsibilities of running the lighthouse for several months before a new keeper could be appointed.

Rebecca Flaherty, Sand Key Lighthouse, Florida

Due to shallow coral reefs and sandy shoals, the Florida Keys were notoriously dangerous for vessels, so much so that for many years wreckers made a living off rescuing cargo and people from stranded ships that had run aground. Safety was improved by the installation of a number of lighthouses and other navigational aids all along the reef tract, now protected by Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. One of the earliest was Sand Key Lighthouse, about seven miles southwest of Key West, which was built in 1828.

John and Rebecca Flaherty arrived in 1827 when he was appointed as the second keeper of the lighthouse. Originally posted to a lighthouse in the more distant Dry Tortugas (now Dry Tortugas National Park), John was noted as perhaps not being the best keeper and Rebecca was unhappy, writing to the First Lady (at the time the President appointed the keepers) about the loneliness, heat, bugs, and generally unpleasant conditions that came with living on a remote tropical island. John was reassigned to the Sand Key Lighthouse, which was much closer to Key West. Rebecca was presumably more satisfied, or perhaps had no other options, for when John fell sick in 1828, she took up his responsibilities and when her husband died in 1830, she was officially appointed as the keeper. She wed Captain Frederick Neill in 1834 and, as was customary when a woman lighthouse keeper remarried, was removed from her position. She and her family returned north to Baltimore in 1836.

Laura Hecox, Santa Cruz Lighthouse, California

Overlooking Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, we find the story of a woman devoted to the ocean. The Santa Cruz Lighthouse stood on the left bank of the entrance to Santa Cruz Harbor from 1869 to 1941, and during that time, it had only three keepers. The first, Adna Andress Hecox, kept the lighthouse for 14 years, until 1883 when he retired. The third and last keeper was Arthur Anderson, who oversaw the lighthouse for 25 years from 1916 until its decommissioning in 1941. In between, with the longest tenure, was Laura Hecox, daughter of Adna Hecox, who was lighthouse keeper for 33 years.

Laura grew up helping her father tend the lighthouse and, by all accounts, loved the sea, turning to it for solace in a childhood plagued with illness. She became a gifted naturalist and voluminous collector of natural history specimens, wandering the cliffs, beaches, and intertidal zone of the Santa Cruz region her entire life. Today a cove not far from where the lighthouse used to stand is named in her honor and what started from her collections housed in the basement of the public library has grown into the Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History.

Julia Williams, Santa Barbara Lighthouse, California

Further down the coast, another lighthouse stood guard overlooking the California Channel and what would become Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary. Julia Williams spent an incredible 50 years at the Santa Barbara Lighthouse, ten as the wife of its first keeper Albert Williams, and then the last 40 as the official keeper herself. As the city of Santa Barbara grew, she was in later years, according to the Santa Barbara Maritime Museum, a draw for tourists as much as the area's beautiful shorelines and newly developed train routes and luxury hotels. Isolated, raising five children, and with uncertain supplies of water, food, and fuel, Julia nevertheless faithfully kept the light until an injury when she was 81 forced her retirement in 1905. Why did she stay so devoted to the lighthouse? Perhaps her c. 1890 quote relayed by the Santa Barbara Maritime Museum has the answer: "I've never had the time to grow old. I've been too busy…Monotonous or tiresome? Why no, I've never found it so. We have the sea for company always, and I have been happy and always contented here."

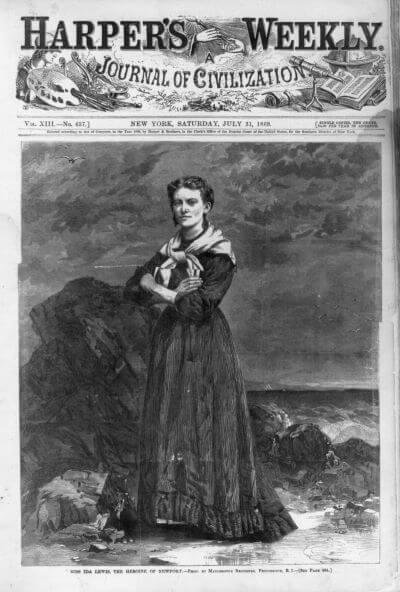

Remembering Idawalley Lewis

Although she wasn't the keeper of a lighthouse near what is now a national marine sanctuary, Idawalley Lewis was the most famous female lighthouse keeper in U.S. history. She tended the Lime Rock Lighthouse in Rhode Island for 54 years, first with her parents starting at age 15 in 1857 and then as official keeper starting in 1879 until her death in 1911. She was credited with saving at least 18 lives and was famed for her bravery, endurance, and dedication, so much so that she was awarded the Gold Lifesaving Medal by the Lighthouse Service and was visited by President Ulysses S. Grant in 1869. Image: Cover of Harper's Weekly, July 31, 1869 issue, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

A Continuing Vigil

Today lighthouses are still an important component of our navigation safety system though nearly all of the approximately 800 are automated. They also remain important parts of our maritime cultural landscapes, where keepers—women and men both—rose to the challenge of isolation, hard work, and valiant vigils to keep mariners and ships safe in dangerous waters.

Elizabeth Moore is the former senior policy advisor for NOAA's Office of National Marine Sanctuaries.