For I Knew a Ship from Stem to Stern

By Elizabeth Moore

February 2017

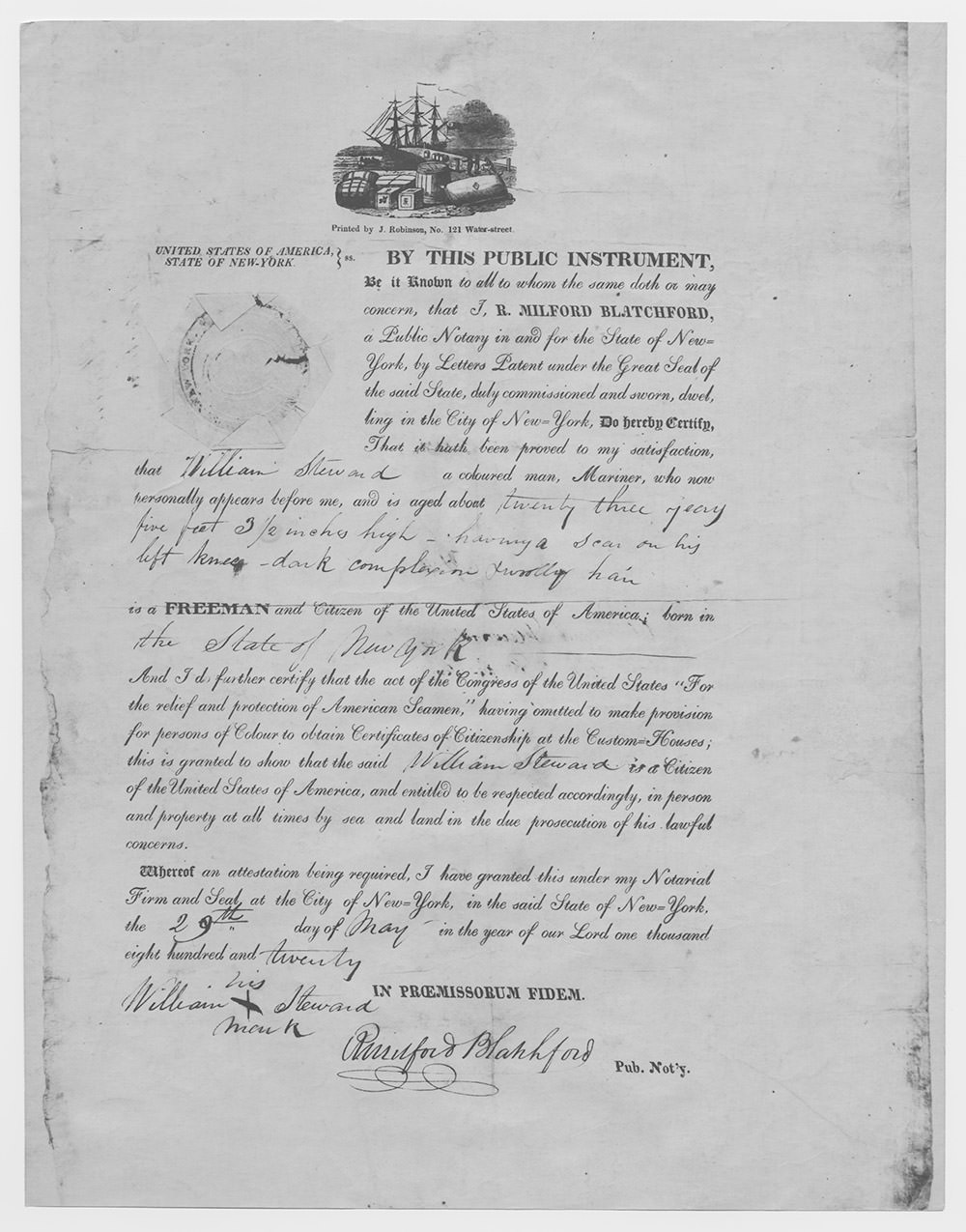

In 1838, at about 20 years of age and with two escape attempts already behind him, Frederick Douglass was working as a caulker in the Baltimore shipyards, pounding hemp into the seams of wooden ships and pouring hot pitch to make them waterproof. It was tedious and difficult work, but would help him in two ways: first, handing over his wages to his owner would drive him to try for a last, successful escape to freedom, and second, his intimate knowledge of ships and sailing would help him in that escape. In September of that year, he boarded a train carrying borrowed papers from a free African-American sailor and dressed in mariners' clothing. "My knowledge of ships and sailor's talk came much to my assistance, for I knew a ship from stem to stern, and from keelson to cross-trees, and could talk sailor like an old salt," he wrote in his memoirs in 1882. Some strategy, luck, and "kind feelings…towards those who go down to the sea in ships" helped him reach New York, and freedom, a day later. He would spend the rest of his long life—agitator, author, diplomat, orator—fighting on behalf of freedom and equality for African-Americans.

Douglass's experience was not entirely out of the ordinary. Maritime industries were rife with the same injustices and brutalities faced by African-Americans in every aspect of American society, but they still provided better work opportunities than terrestrial occupations, and sometimes even a chance for freedom. Slaves and freeborn African-Americans built and sailed ships, harvested fish and shellfish from the Atlantic as Chesapeake watermen and fishers, and risked dangerous seas in search of whales. Our nation's maritime history – and the history of many of our national marine sanctuaries – is intertwined with the stories of many peoples, including those of forcibly-transported and enslaved African-Americans.

African-Americans were members of merchant and naval crews dating back to before the Revolutionary War, including as sought-after pilots with a respected knowledge of the inland waters and outer coastal waters of the Atlantic seaboard. Moses Grandy, a slave born in 1786, used the money he earned as master of canal boats navigating the Great Dismal Swamp Canal in Virginia and North Carolina to buy his freedom, and earnings from later sea voyages to buy that of his wife; twice before, his owners had taken his earnings to buy his freedom yet still kept him enslaved. In his memoir he wrote about his feelings on obtaining freedom, "I felt to myself so light, that I almost thought I could fly, and in my sleep I was always dreaming of flying over woods and rivers." Born in 1745, Olaudah Equiano was another slave who purchased his freedom with earnings from maritime trade. Despite the memory of the horrors of the slave ship that transported him from his native land, he spent his later free years still sailing; "I was perfectly happy; for the ship, master, and voyage, were entirely to my mind," he wrote on embarking on another sea venture.

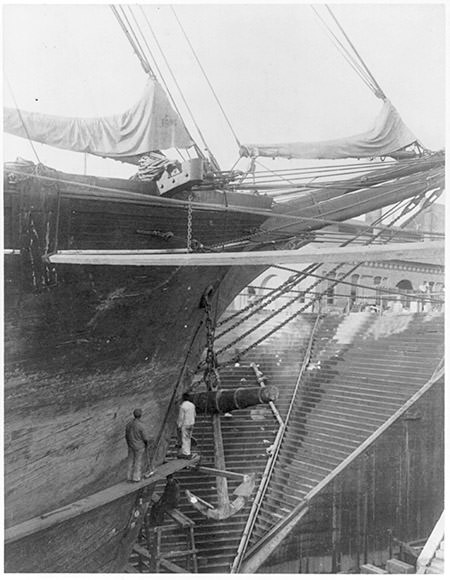

Sometimes the employment of African-Americans in maritime trade helped build entire communities. One example is Newport News, Virginia, the gateway community to and headquarters of Monitor National Marine Sanctuary. After the Civil War, Newport News had a predominantly African-American population. With the founding of the Newport News shipyards, many African-Americans went to work building ships, a tradition that continues today in the city's modern shipbuilding companies. The community thrived, building churches, libraries, and schools, and producing lawyers, doctors, and noted entertainer Ella Fitzgerald.

The hiring of so many African-Americans into shipbuilding in Newport News led the trend for other shipyards in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For example, African-Americans during World War I made up about 20 percent of the workforce at the Hog Island, Pennsylvania shipyard, at the time the largest in the world. Many of the vessels constructed at Hog Island, the famed Ghost Fleet, now rest in the waters of Mallow's Bay, a site currently undergoing the sanctuary designation process.

African-American history is also intertwined with that of Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary. Today, the sanctuary protects humpback whale feeding grounds, and whales are protected throughout all federal waters. But Massachusetts was once the world's whaling epicenter. Even more than other maritime trades, because of its hazardous nature and ever present demand for workers, whaling provided more opportunities and better-paying employment for African-Americans. They served on crews, captained ships, and contributed to technological advances; blacksmith Lewis Temple invented a toggle-headed harpoon that was better than its predecessors which tended to slip free of whale blubber.

Leading up to the Civil War, about 3,000 African-Americans were employed on whaling ships in various roles. One of them, John Thompson, born into slavery in 1812 in Maryland, escaped and made his way north but feared recapture, writing, "I finally concluded best for me to go to sea." He spent several years on the whaler Milford, writing on the taking of whales and the exotic lands they visited. He ends his memoirs likening his strong Christian faith to a voyage on perilous seas.

Like shipbuilding, sailing, and whaling, taking oysters and crabs from the Bay—the mainstay of Chesapeake watermen—offered a relatively good living for African-Americans, albeit it one fraught with prejudice and legal barriers. Early 19th century laws designed to limit the ability of free African-Americans to participate and succeed in many maritime trades (such as not being able to serve as captain on a boat of any significant size) gave way to equally repellent Jim Crow laws in the mid-20th century. Despite such impediments, African-Americans continued to practice their traditional craft with an abiding love into the modern age. In a 1998 interview with Maryland Sea Grant, one veteran waterman said, "Nothing like working on the water for me. You can get up in the morning and see the sun when it's coming up."