Listening to the Ocean in the Time of COVID-19

By Anne Smrcina

Right whales are one type of animal detected in sanctuary acoustic studies. Photo: Peter Flood

March 2021

Like students, office personnel, and late-night TV hosts, scientists are navigating the new world of remote work. Despite closed laboratories and cancelled research expeditions, acoustic science at Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary continues in the time of COVID-19. Insights garnered, techniques perfected, and lessons learned during these challenging times have helped to advance science and will likely change the ways some research is done in the future.

To protect crews from possible health risks, as well as to avoid seasonal weather-related barriers to field work such as wind, waves, and snow, researchers instead relied on using bottom-mounted stationary listening buoys and autonomous underwater vehicles equipped with hydrophones to collect data. Scientific instruments cannot contract viruses and do not get seasick, and are comparatively more cost-effective than vessel-based operations. Additionally, by maintaining the scientific integrity of multi-year data sets, the researchers can now compare conditions from past years to what is happening during the months of the pandemic. The work is part of a multi-sanctuary research effort co-led by NOAA and the U.S. Navy -- the Sanctuary Soundscape Monitoring Project (SanctSound).

For Dr. Leila Hatch, the sanctuary’s marine ecologist and co-lead for the SanctSound project, “In the murky and often dark marine environment of New England’s waters, we now find, just as the animals have always known, that listening can be as, or even more, effective than seeing. Listening has become a way for the sanctuary and its partners to monitor what is going on offshore during this time of social distancing.”

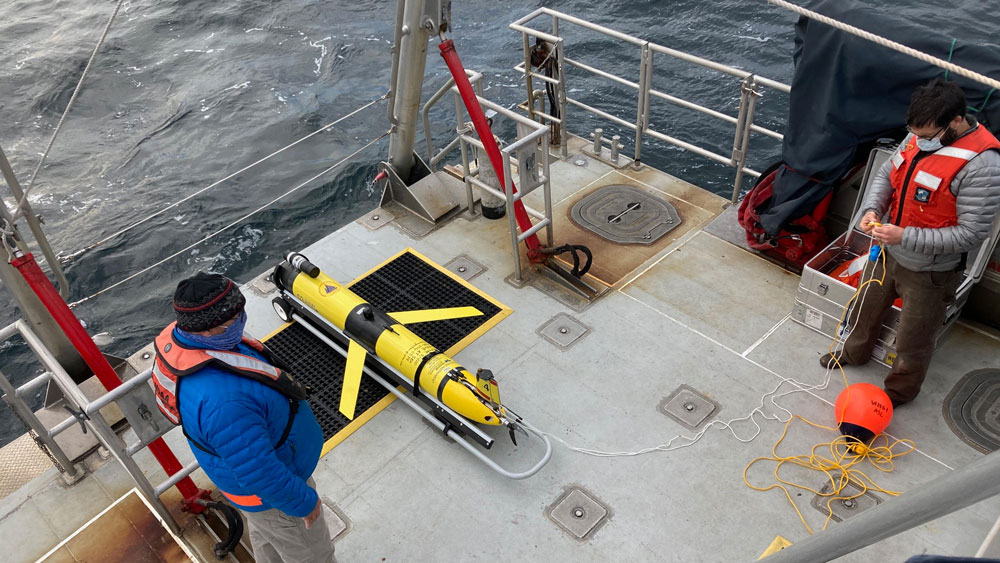

A Glider Follows a Programmed Path

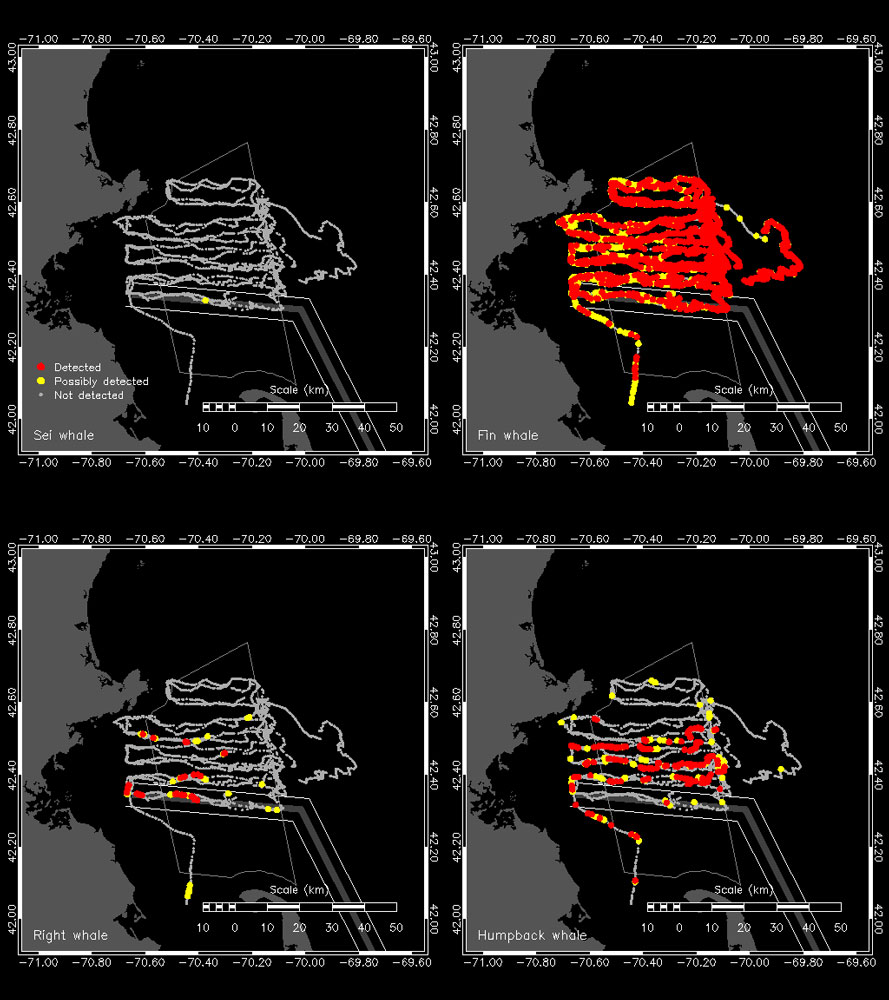

A bright yellow, torpedo-like glider off the Massachusetts coast patrols the sanctuary, listening for sounds that flood this environment, including vocalizations from animals and human-caused noises from ships and other activities. The deployment is a collaboration between SanctSound and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Instruments installed in the glider analyze immediately what is heard and transmit those findings via cell phone to the research team when the glider surfaces.

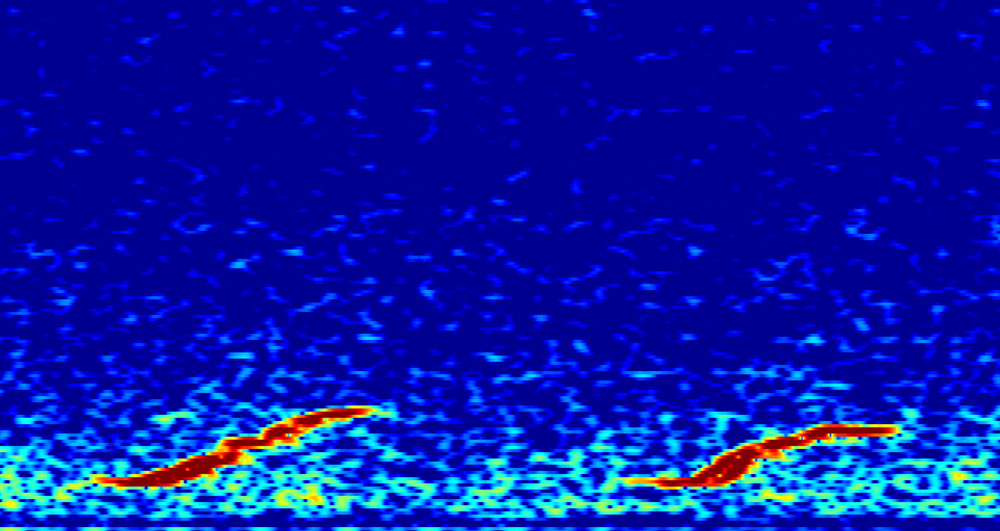

Recently, near real-time detections of North Atlantic right whale upcalls (a distinctive vocalization) in the sanctuary led to the designation of a Right Whale Slow Zone. This conservation action by NOAA, which recommends ships reduce speeds to less than 10 knots, was accomplished without any human presence on the water. Past studies have shown that slower ship speeds offer whales a better chance of avoiding potentially lethal strikes. The Right Whale Slow Zone program from NOAA Fisheries is similar to the older Dynamic Management Areas (DMA) program, but now uses acoustic detections of right whales in addition to the visual sightings used for DMAs.

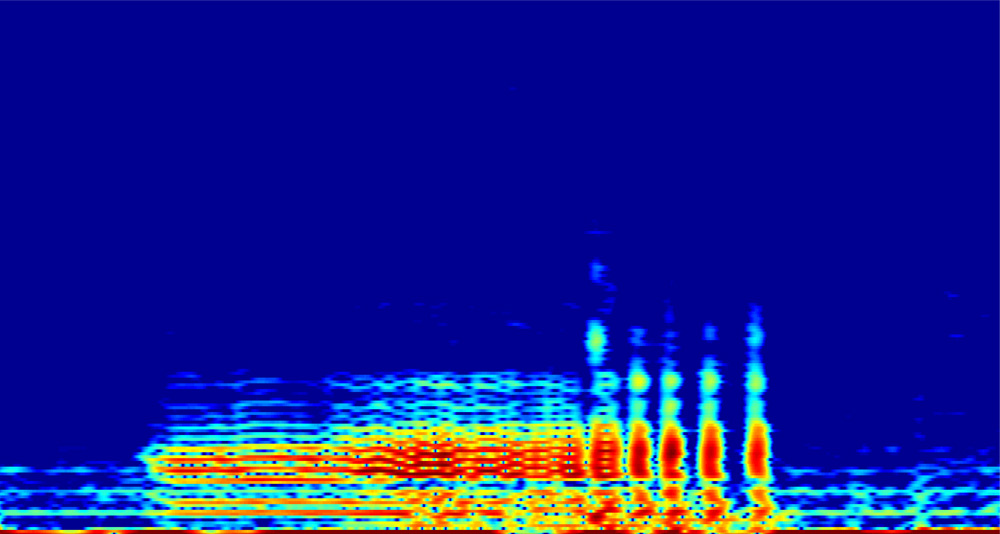

But whale detections are not the only job for this stealthy technology. The glider, uncrewed and programmed in advance, follows a series of GPS waypoints, on a path that takes it over habitat used by commercially important haddock and cod -- the former species in relatively good numbers, the latter considered overfished. Researchers can listen remotely for the unique grunts and knocks of male cod and haddock that are indicative of spawning ground activity. Determining where and when these fish are mating may lead to management strategies that keep haddock numbers up and support efforts to protect cod reproduction. Thanks to this remote technology, no humans are needed at sea to detect this important life cycle event.

Listen to North Atlantic right whale song. Photo: Peter Flood

Listen to the the thumps and knocks of Atlantic haddock. Photo: Peter Auster/UConn

Listen to the grunts and knocks of Atlantic cod. Photo: Doug Costa/NOAA

Listening Posts Collect Long-Term Data

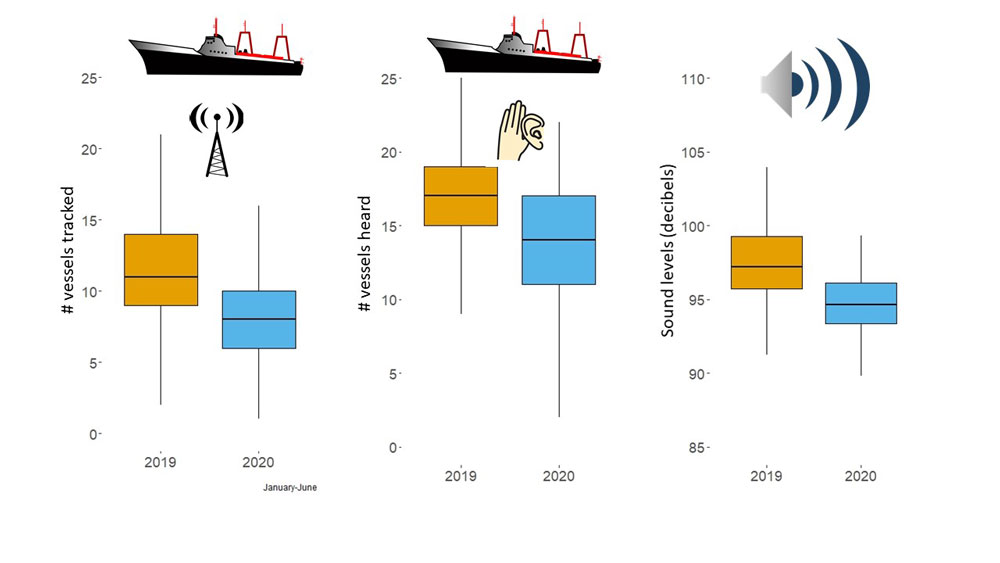

Mobile technology, such as gliders, offers advantages by covering large regions, however, stationary monitoring allows researchers to compare conditions over time in a few strategic places. There are three underwater recording stations in Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary that are part of SanctSound monitoring. These stations are used to understand levels of sound in the sanctuary , including natural sources (e.g., animals and environmental forces, like wind, waves, and rain), and man-made sources (e.g., vessels and offshore activities). Measurements are made over several years, allowing scientists to link changes in what they hear to events that change human activities offshore. For example, in the first five months of 2020, levels of noise recorded at low frequencies (low “tones”) in the northwestern sanctuary were reduced compared to the same period in 2019. Scientists examined the numbers of vessels tracking close to and heard on this recorder and found that both were reduced in 2020, during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. These preliminary findings have led to new partnerships to explore the effect of this reduced noise on marine animals in the sanctuary.

Many Hands, But Little Contact

Although the acoustic monitoring equipment is designed to operate remotely, the glider still needs to be deployed and retrieved at the beginning and end of its programmed path, and the recording units in the stationary, anchored buoys need to be serviced and storage media swapped out.

“The beauty of these systems is that the work can be done with a minimal crew on a small boat,“ says Dr. Timothy Rowell, a primary operational and analytical lead for SanctSound, based at NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center. “It still takes a village to do this science, but this technology plays its role gathering information for us remotely, serving as our ears when we can’t be there ourselves.”

While long-term, ocean-going research missions will once again be planned when health and safety restrictions ease, the lessons learned during the pandemic may lead to major changes in how we do science at sea. “We are discovering that a better understanding of the sound environment can provide us with insights previously unimagined in the past,” notes Dr. Hatch. “In the ocean, where light disappears with depth and rich, productive northern waters can be murky, hearing is a more essential sense than sight for many ocean animals, and has become a primary research tool for humans, too.”

Anne Smrcina is the education coordinator for Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary.