Presidents and Parks: The Untold Story of the Ocean Legacy of the Nation’s Leaders

50th Anniversary Sanctuary Signature Articles

By Elizabeth Moore | November 2021

My Sporting Proclivities

On an early May Monday morning in 1768, George Washington—36 years old, war veteran, elected official—set out to spend the day pursuing one of his favored hobbies, angling in the Potomac River that ran along the lands and farms of Mount Vernon. He may have enjoyed the quiet of a pleasant spring day, but he went home empty-handed. Later he wrote in his diary: “Fishing for Sturgeon from Breakfast to Dinner but catchd none.”1

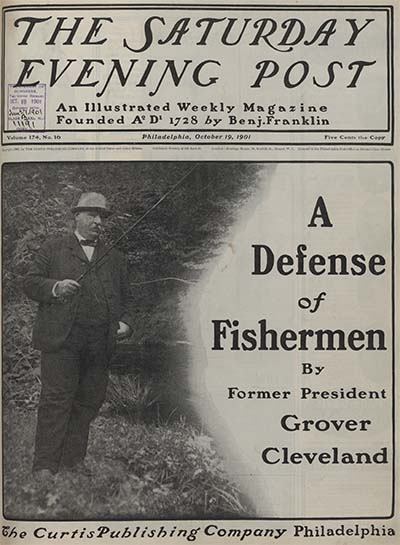

Many who followed Washington in the presidency were ardent outdoor enthusiasts as well: hunters, anglers, and sailors who enjoyed taking time away from politics for simpler pleasures. Grover Cleveland, for example, wrote Fishing and Shooting Sketches in 1906, in which he defended himself against criticism of his leisure pursuits during his presidency: “I am sure it is not necessary for me, at this late day, to dwell upon the fact that I am an enthusiast in my devotion to hunting and fishing, as well as every other kind of outdoor recreation. I am so proud of this devotion that, although my sporting proclivities have at times subjected me to criticism and petty forms of persecution, I make no claim that my steadfastness should be looked upon as manifesting the courage of martyrdom. On the contrary, I regard these criticisms and persecutions as nothing more serious than gnat stings suffered on the bank of a stream.”2

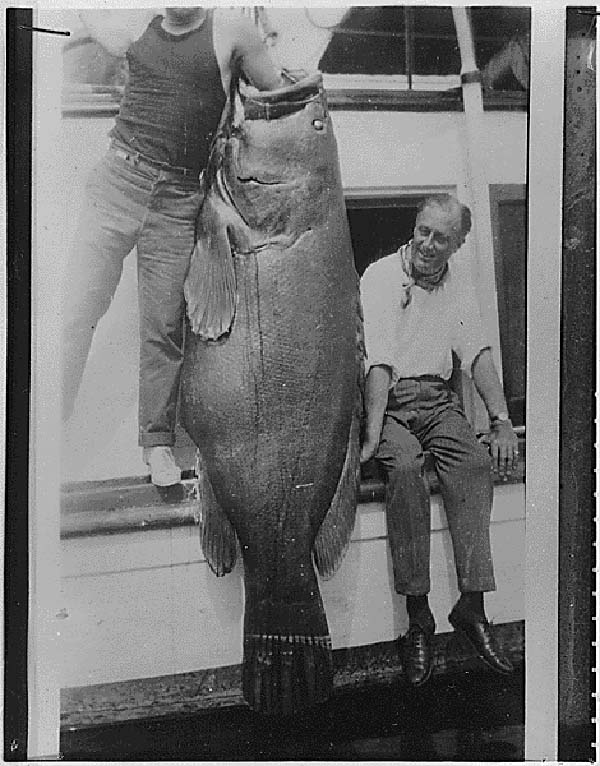

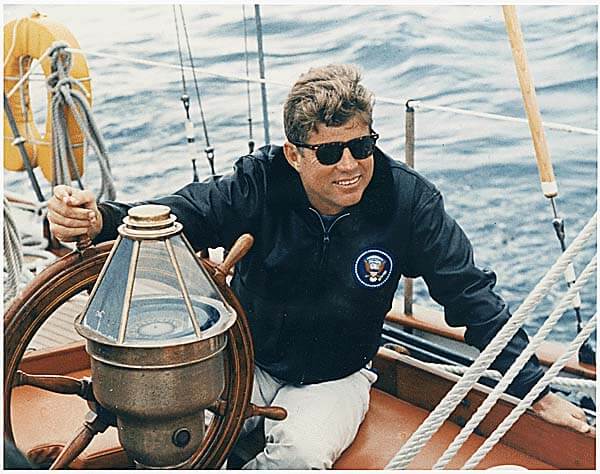

Herbert Hoover was known as “The Fishing President,” and Franklin Delano Roosevelt was almost as well-known for his love of the outdoors as he was for his political accomplishments. He sometimes combined them, taking British Prime Minister Winston Churchill fishing at Camp David and using the presidential yacht Sequoia for secluded political discussions and negotiations (as did Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, and Ford after him, before President Carter ordered the sale of the vessel in 1977). Dwight D. Eisenhower and Jimmy Carter were also both fishermen, Carter often taking to the waters during vacations in various coastal areas of the U.S., including at Sapelo Island, inshore of Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary in Georgia. John F. Kennedy was a lifelong sailor and skilled yachtsman; his sloop Victura, a 15th birthday present from his father, sits in front of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston.

Many presidents throughout U.S. history have combined their love and enjoyment of the outdoors with environmental action but the first president who might be called conservation-minded was Andrew Jackson. He was the first president to sign legislation setting aside land for conservation and recreation, approving the creation of the Hot Springs Reservation (now Hot Springs National Park) in Arkansas in 1832. Forty years later Ulysses S. Grant signed the legislation that created Yellowstone National Park in 1872, the nation’s and, arguably the world’s, first modern national park.

The following presidents built well-known and celebrated conservation legacies. Theodore Roosevelt signed the Antiquities Act and put it to work by creating 18 monuments under its authority; he also created the first national wildlife refuges and established the National Wildlife Refuge System in 1903, now 568 units strong. Woodrow Wilson created 13 monuments and presided over the 1916 founding of the National Park Service, which now boasts 423 parks of various types. Succeeding presidents created new parks under these laws, most notably Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who also established the Civilian Conservation Corps as part of his New Deal; the corps was instrumental in building infrastructure in many national parks and planting billions of trees, among other achievements. Among modern presidents, Jimmy Carter, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama left extensive, outstanding conservation legacies that protect some of the most important lands, naturally, culturally, or historically, of the nation. But few understand the role of the presidency in shaping ocean conservation and protected areas. Let’s take a look, starting with the 1869 to 1877 presidency of Ulysses S. Grant.

The following presidents built well-known and celebrated conservation legacies. Theodore Roosevelt signed the Antiquities Act and put it to work by creating 18 monuments under its authority; he also created the first national wildlife refuges and established the National Wildlife Refuge System in 1903, now 568 units strong. Woodrow Wilson created 13 monuments and presided over the 1916 founding of the National Park Service, which now boasts 423 parks of various types. Succeeding presidents created new parks under these laws, most notably Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who also established the Civilian Conservation Corps as part of his New Deal; the corps was instrumental in building infrastructure in many national parks and planting billions of trees, among other achievements. Among modern presidents, Jimmy Carter, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama left extensive, outstanding conservation legacies that protect some of the most important lands, naturally, culturally, or historically, of the nation. But few understand the role of the presidency in shaping ocean conservation and protected areas. Let’s take a look, starting with the 1869 to 1877 presidency of Ulysses S. Grant.

A Special Reservation for Government Purposes

Grant became president in the turbulent, traumatic aftermath of the Civil War when the rebuilding and healing of a nation was paramount. But one issue in the distant Pribilof Islands needed immediate attention. With the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867, Americans rushed in to make their fortunes in the expansive new territory, including from the fur seals in the Pribilof Islands. In the first two years, sealing companies took an estimated 200,000 to 300,000 skins, decimating a population that had been considered thriving before the transfer of power to the U.S. Conditions worsened so rapidly that by 1869, the military was sent to the islands to protect the herds of fur seals and, although prompted by mainly economic motives, created possibly the first modern underwater park in the world. The islands of St. Paul and St. George, and the waters around them, became a “special reservation for Government purposes,” as declared by a joint resolution of Congress.3 The reservation pre-dated Yellowstone National Park by two years.

A lack of enforcement in the reserve and of harvest limits, however, resulted in a continued slaughter of the fur seals until an international agreement in 1911 and subsequent laws and conventions at last provided vital protection that helped the species survive. The fur seals remained important enough to the nation that Grover Cleveland, in his fourth annual address to Congress in 1888, stated: “My endeavors to establish by international cooperation measures for the prevention of the extermination of fur seals in Bering Sea have not been relaxed, and I have hopes of being enabled shortly to submit an effective and satisfactory conventional project with the maritime powers for the approval of the Senate.”4

The Pribilof reserve might have failed as such but it was prescient in its concept that a mechanism for protecting land—setting it aside as a park—could have as much utility in the sea. After all, the boundaries of the nation extend for two hundred miles out into the ocean; the U.S. is roughly 54% water and 46% land. The model presented by the Pribilof reserve by extending the protection from the land to the sea held sway for decades to come.

Preserve From Destruction

In 1913, four years after leaving office, Theodore Roosevelt prepared his autobiography, outlining the legacy he left the nation. Among his achievements, he felt the most important included his work in protecting wildlife and preserving wild lands and waters: “Even more important was the taking of steps to preserve from destruction beautiful and wonderful wild creatures whose existence was threatened by greed and wantonness.” In 1903, he designated the first protected area to combine lands and waters since the 1869 Pribilof reserve: the Pelican Island National Bird Reserve (the first of its kind and now Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge); he followed that shortly thereafter by placing Midway Atoll, now part of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, under naval control. He issued an executive order six years later creating the Hawaiian Islands Bird Reservation around the islands from Nihoa to Kure. These were the first presidential actions to protect an area later to be part of the sanctuary system. In all, Roosevelt created 51 bird reserves, five national parks, and 18 monuments, and, in 1906, signed the Antiquities Act which was later used, as we will see, to substantially expand protection of U.S. waters.

But first the Antiquities Act was used to protect wide swathes of land, and sometimes some adjoining water areas, in William Howard Taft’s creation of 10 monuments, Woodrow Wilson’s 13, Warren G. Harding’s eight, and Calvin Coolidge’s 13, including Glacier Bay National Monument in 1925 (now Glacier Bay National Park) which included more than 950 square miles of water. Woodrow Wilson also, in 1916, created the National Park Service. Herbert Hoover, the Fishing President, created nine monuments. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a distant cousin of Theodore Roosevelt, was his heir not only in serving as President but in creating a grand conservation legacy for the nation, one that included more extensive water areas than any president before him.

FDR built on Theodore Roosevelt’s Hawaiian protections when he issued a presidential proclamation in 1940, changing the name of the Hawaiian Islands Bird Reservation to the Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge and extending its protection to all wildlife. The action capped a number of years of creating parks with extensive water components, including Everglades National Park in 1934, Fort Jefferson National Monument in 1935 (now Dry Tortugas National Park), and Isle Royale National Park in 1940, more than 1,500 square miles of water combined. Subsequent presidents followed his pattern, adding land-and-water combined parks in the following three decades. Harry S. Truman only created one monument—1953’s Cape Hatteras National Seashore—but it included 12 square miles of adjacent ocean. His successor Dwight D. Eisenhower, an avid fisherman, created Virgin Islands National Park in 1956, with its 9 square miles of surrounding ocean.

John F. Kennedy, in the three years of an administration cut short by assassination, added three new national seashores (Point Reyes, Cape Cod, and Padre Island) and Buck Island National Monument. His successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, also favored national sea- and lakeshores and created four of them: Fire Island (1964), Assateague Island (1965), Cape Lookout (1966), and Pictured Rocks (1966). But FDR’s record of protecting waters in parks stood until 1972, when a president who ultimately disgraced himself nonetheless carved out his place in the marine conservation legacy of the nation.

Glory and Majesty and Life of the Shining Seas

Richard Nixon was content to create parks with water components as his predecessors had, including Cumberland Island and Gulf Islands national seashores, Golden Gate and Gateway national recreation areas, and Sleeping Bear Dunes and Apostle Islands national lakeshores, with a collective 300 square miles of water, but he didn’t want to sign the legislation that would ultimately be the foundation of the nation’s oldest and largest network of underwater parks. “We share the oceans,” he wrote in October 1972 of signing the Marine Mammal Protection Act, “with all who live on this planet. Our actions are part of what we hope and trust will be a global commitment to protect the glory and majesty and life of the shining seas.” Of signing the Coastal Zone Management Act: “...to provide for the rational management of a unique national resource.” Of the Title I provision for controlling ocean dumping of the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act: “...will provide the controls over ocean dumping which have long been a matter of high priority concern for this Administration.” But of Title III of the same act, which created the National Marine Sanctuary Program, he said nothing in his signing statement. He had opposed the addition of Title III to an act that in his mind should only be about ocean dumping, but signed it anyway.

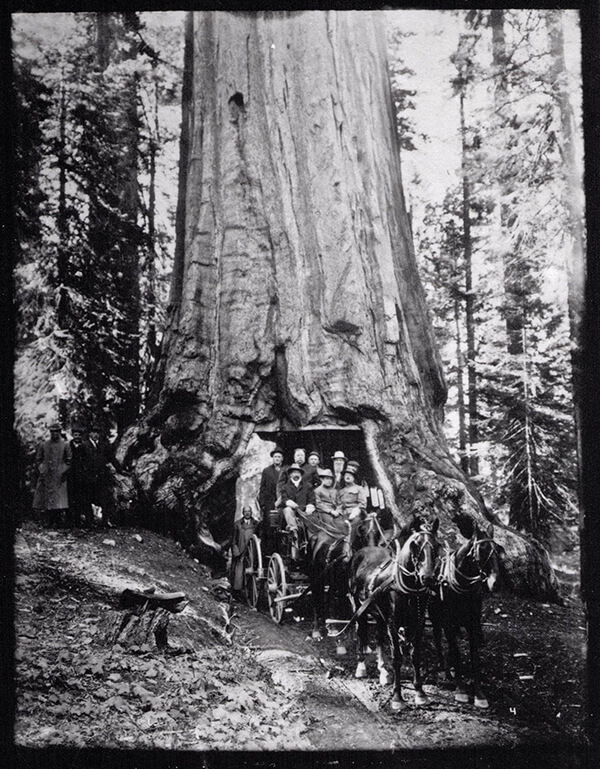

The first national marine sanctuaries were designated under Nixon’s successor Gerald Ford in 1975, the mile-circle around the wreck of the Monitor and Key Largo, 103 square miles centered around John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park in the central Keys and now part of Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Ford knew parks well, having been a summer park ranger in Yellowstone National Park in 1936, which he had recalled as “one of the greatest summers of my life.”5 Ford never created any monuments under the Antiquities Act but he approved a number of parks that included water areas, among them the extensive wetlands and cypress forests of Big Cypress National Preserve in 1974 and gold-sanded beaches of Cape Canaveral National Seashore in 1975.

Jimmy Carter was the first president to take a personal interest in the sanctuary program, highlighting it in his 1977 Environment Message to the Congress: “Existing legislation allows the Secretary of Commerce to protect certain estuarine and ocean resources from the ill-effects of development by designating marine sanctuaries. Yet only two sanctuaries have been established since 1972, when the program began. I am, therefore, instructing the Secretary of Commerce to identify possible sanctuaries in areas where development appears imminent, and to begin collecting the data necessary to designate them as such under the law.” In addition to the 23 parks and monuments (including the water-rich Channel Islands and Biscayne Bay national parks) and 25 wild and scenic rivers Carter oversaw (many as part of the massive Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980), he also added four sites to the burgeoning sanctuary system: Looe Key (now part of Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary), Channel Islands, Point Reyes-Farallon Islands (now Greater Farallones), and Gray’s Reef national marine sanctuaries.

Jimmy Carter’s expansive conservation action slowed during the following administration. One sanctuary was designated, Fagatele Bay National Marine Sanctuary (now National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa), under President Reagan. His successor George H.W. Bush holds the record for most national marine sanctuaries designated during a presidency (six designations). Cordell Bank was the first, followed by Florida Keys, after three successive vessel groundings destroyed thousands of acres of coral. His signing statement for the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and Protection Act made his strong support clear: “Today I take great pleasure in signing H.R. 5909 – a bill that designates 2,600 square nautical miles of coastal waters off the Florida Keys as our nation's ninth national marine sanctuary. The new Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary covers the entire Florida reef tract…My approval of the legislation demonstrates this nation's resolve to preserve ecologically unique ocean areas.” Four more sites were added to the sanctuary system in 1992: Monterey Bay, Flower Garden Banks, Stellwagen Bank, and Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale national marine sanctuaries.

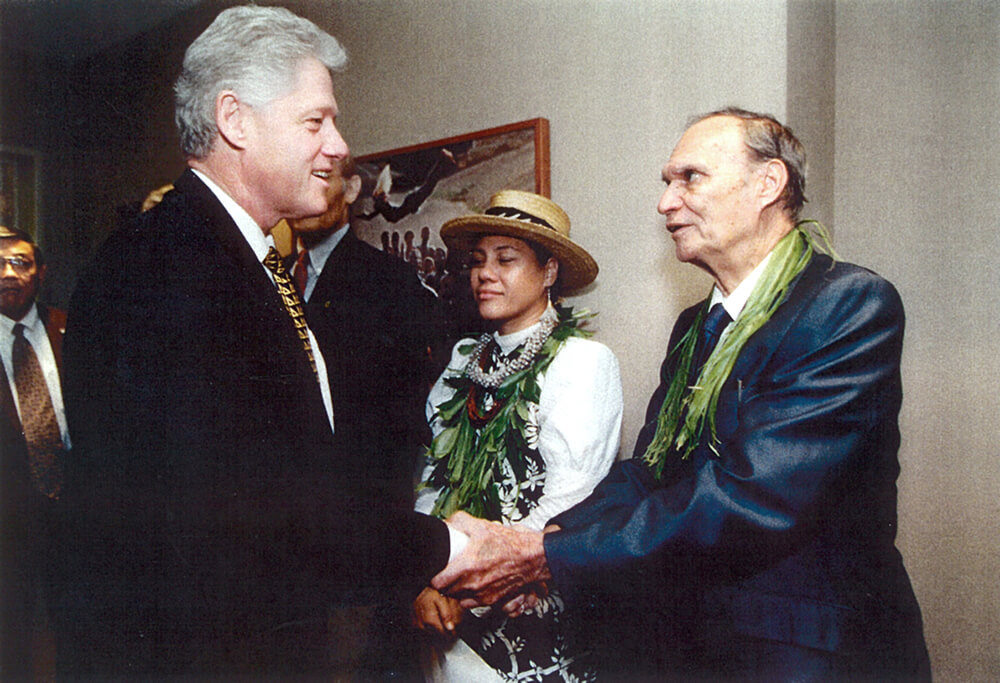

As importantly, the 1992 reauthorization of the sanctuary system’s governing legislation created and strengthened the stand-alone National Marine Sanctuaries Act and added important innovations like prioritizing long-term monitoring, research, and education, adding a consultation requirement for federal agencies, and creating a stand-alone authority for creating sanctuary advisory councils. The Clinton administration added Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary in 1994 and Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary in 1996, but one of Clinton’s final acts in office would set the stage for some of the nation’s largest marine conservation gains in the new millennium.

To Renew The Very Ocean

In December 2000, President Clinton stood before a crowd gathered at the National Geographic headquarters in downtown Washington, DC; many of those attending were dignitaries who’d made the long trip from Hawaiʻi to see the fruition of their long years of work: the protection of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. The president has just signed Executive Order 13178 creating the wholly underwater Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve, a decidedly new use of the almost-century-old Antiquities Act. “For thousands of years, people have risked their lives to master the ocean,” he remarked. “Now, suddenly, the ocean's life is at risk. We have the resources and responsibility to rescue the sea, to renew the very oceans that give us life, and thereby to renew ourselves. Today is an important step on that Road.”

He created another road perhaps without intending to. With the creation of the reserve, the Antiquities Act became an additional tool for creating underwater parks in the nation. Though prior presidents had used the Antiquities Act to create monuments that included water areas (for example, John F. Kennedy created the Buck Island Reef National Monument in the U.S. Virgin Islands in 1961 to preserve it as “one of the finest marine gardens in the Caribbean Sea”), Bill Clinton was the first to use it to create protected areas that were wholly submerged.

Subsequent presidents also liked using the Antiquities Act to create underwater parks. Though George W. Bush initially “froze” the executive order creating the reserve in the early days of his administration when he succeeded Clinton, he came to be an enthusiastic proponent not only of the reserve but of large underwater monuments. In 2006, Bush issued Presidential Proclamation 8031 enlarging and renaming the reserve as Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument; First Lady Laura Bush announced its new name, chosen with the guidance and blessing of Native Hawaiian elders, of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in early 2007. Bush further designated Rose Atoll, Pacific Remote Islands, and Marianas Trench marine national monuments in 2009, collectively protecting tens of thousands of square miles of American waters.

For Generations to Come

On a brilliantly sunny day in September 2016, President Obama stood with a small crowd on Midway Atoll. He had chosen to deliver his remarks on his expansion (to more than 582,000 square miles) of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument within the boundaries of the park itself, the first president to do so. “And so for us to be able to protect and preserve this national monument,” he said, “to extend it and, most importantly, to interact with native Hawaiians and other stakeholders so that the way we protect and manage this facility is consistent with ancient traditions and the best science available, this is going to be a precious resource for generations to come.” Obama created 26 monuments during his two terms, including Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument off the coast of New England in 2016.

Though Obama made extensive use of the Antiquities Act, his administration also saw a number of substantial expansions of existing sanctuaries under the National Marine Sanctuaries Act. Though some sanctuaries had been minorly expanded over the years (the addition of Stetson Bank to Flower Garden Banks by Congress in 1996 and of the Tortugas Ecological Reserve to Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary by administrative action in 2001), the sanctuary system had never before administratively undertaken major expansions until 2009, when Davidson Seamount—whose importance became apparent by research expeditions to the submerged mountain in 2002 and 2006—was added to Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, expanding its size by 775 square miles. An even larger expansion in 2012 turned the tiny Fagatele Bay National Marine Sanctuary into the largest sanctuary in the network, renamed National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa. A threefold enlargement of Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary in 2014, driven by community interest, protected even more important shipwrecks. The 2015 expansion of Cordell Bank and Greater Farallones national marine sanctuaries extended their protection to important offshore and coastal resources. In the Gulf of Mexico, a nearly three-fold expansion of Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary in 2021 extended protection to additional essential habitats for commercially and recreationally important fish, as well as habitats for threatened and endangered species, while also minimizing potential user conflicts. Together, these expansions added a significant amount of new protected water to the underwater parks of the nation.

Everything Honorable and Glorious

In 1781, as the Revolutionary War was winding down, George Washington wrote the Marquis de Lafayette: “Without a decisive naval force we can do nothing definitive. And with it, everything honorable and glorious.” He recognized, from early on, the strategic military importance of the ocean to a newborn nation. His successors to the presidency would also understand the ocean’s crucial role in providing for the U.S., in sustenance, economic development, recreation, and national identity. Many of his successors would take action to protect it: creating conservation legacies are a hallmark of modern presidencies. The protected waters that have been bequeathed to us, and the stewardship we provide today, will leave a better world for generations to come.

References

1. The Writings of George Washington, Vol. II (1758 -1775) edited by Worthington Chauncey Ford, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1889.

https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/washington-the-writings-of-george-washington-vol-ii-1758-1775?q=fish#Washington_1450-02_309

2. Fishing and Shooting Sketches by Grover Cleveland, The Outing Publishing Company, New York, 1906.

https://archive.org/details/fishingshootings00clev/page/n9/mode/2up

4. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/fourth-annual-message-first-term