The Power of Wow: A Half-Century of Discovery in Ocean Parks

50th Anniversary Sanctuary Signature Articles

By Elizabeth Moore | April 2022

Photo: The Perseid meteor shower was captured in 2015 over West Virginia. Credit: Bill Ingalls/NASA

The Value of Science

From even before the passage of the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act of 1972 (MPRSA), it was clear that science was intended to be central to the creation and management of national marine sanctuaries. "Scientific value" is one of the qualities of an area that helps judge its special national significance and thus its fitness as a sanctuary, and in 1984 Congress added a mandate to the MPRSA for NOAA to conduct research as necessary to meet the purposes of the act. From these beginnings the sanctuary system has developed an outstanding science legacy. One measure of its achievements is the half-century of discovery of new things—such as shipwrecks, artifacts, species, habitats, and natural processes—that inspire, amaze, and awe us. Let's explore the power of wow!

Seeing the World in a New Way

Sometimes a new discovery will answer a question we've asked, or didn't even know to ask. Questions like: How does that happen? Why is this here and not there? What does that do? One of those unexpected answers came in 1990, when divers in what would become Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary witnessed something scientists had never seen in the Gulf of Mexico or Atlantic basin before: the mass spawning of coral reefs. Usually occurring around full moons in August, some combination of cues from water temperature, light and chemical triggers, and lunar and solar cycles cause certain species of coral to release eggs and sperm in a dense storm that is their method of reproduction. Today, this underwater blizzard is regularly observed in coral ecosystems around the world.

This same sanctuary has yielded other discoveries that surprised scientists, including new species (we'll get to those in the next section), but also new habitats and processes. Even the presence of coral reefs in such deep, cold water was a surprise to scientists first exploring the area in the 1950s and was one of the primary reasons the area became a sanctuary. A new habitat type of mud volcanoes with gas seeps was documented for the first time on the Secrets of the Gulf Expedition in 2007. In these deep sea habitats, methane gas creates a cone of sediment—resembling a volcano and sometimes reaching more than 100 feet high—as it bubbles up through the seafloor.

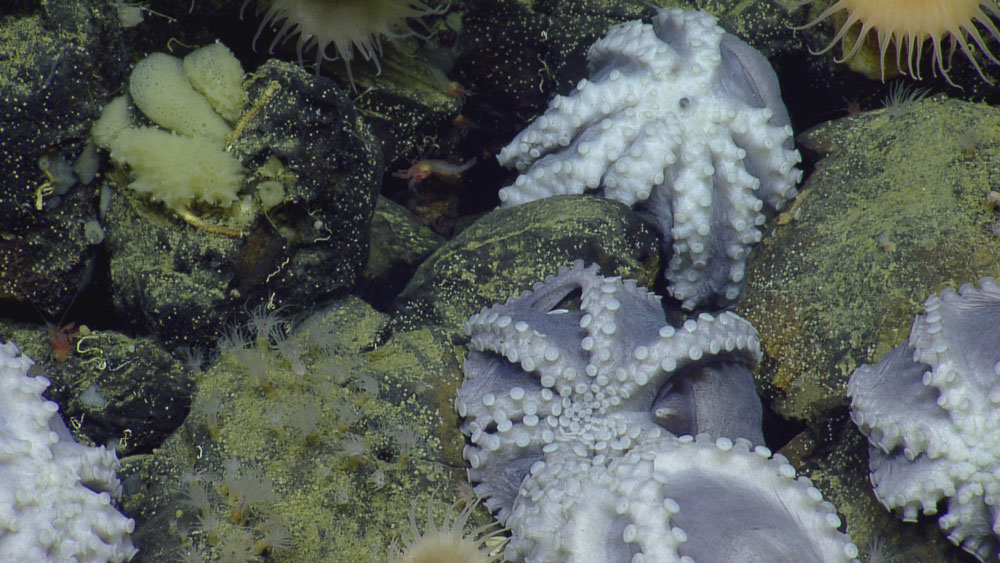

Two years later, tracking data from tagged whale sharks helped researchers discover the migration of whale sharks between the northwestern Gulf of Mexico and Mesoamerican reefs. More recently, in 2018, one of our Dr. Nancy Foster Scholars, Josh Stewart, helped solve the mystery of where manta rays spend their youth, when he confirmed that the sanctuary is an important nursery habitat for juveniles. The same year, another sanctuary had an unexpected wildlife finding too when researchers in Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary observed what they called deep-sea "octopus gardens". Underwater video taken by a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) from E/V Nautilus showed thousands of octopuses brooding nests of eggs along a heat vent near the base of Davidson Seamount, a phenomenon that has rarely been seen before.

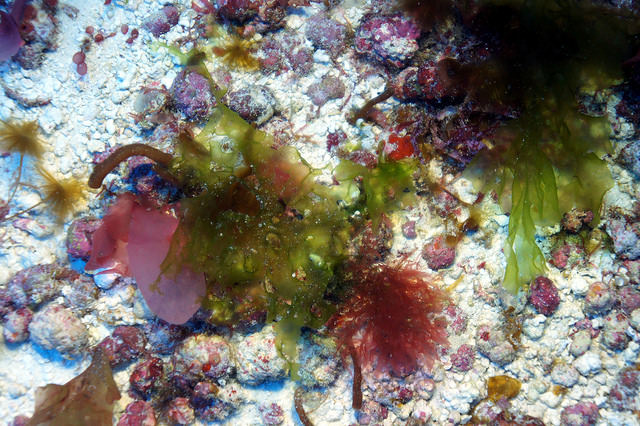

Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary has been the site of many discoveries since its designation in 1992. Another site in the sanctuary system, Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, has had an amazing track record of discoveries too, including a number of new species. It too has been the site of the discovery of a new type of habitat, in this case lush beds of Sargassum below depths of 300 feet, discovered in 2019 by divers using rebreather technology. Sargassum, a kind of brown seaweed, is usually found in tidepools and much shallower reef systems in Hawai‘i, so observing it so deep was an unexpected finding. The monument also holds a unique record in science: in 2015, off Kure Atoll (in the extreme northern end of the monument), scientists documented 100% species endemism, meaning each of the 22 species they documented was native to Hawaiian waters and found nowhere else in the world. It was the first time that such total endemism had been found in the marine realm.

Adding New Life to the Biodiversity Inventory

Biodiversity is the variety of life that can be found in a given area. While experts don't agree on the total number of species we have here on our ocean planet, they do agree that we aren't even close to knowing all that exist. Any opportunity to add to the knowledge of our biodiversity is a cause for celebration. As we continue to explore within the waters of national marine sanctuaries, we continue to uncover new species and more pieces of our planet's biodiversity puzzle. One of the species discovered in Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary in 1977 is colorful enough to be a party...and was named for one—the Mardi Gras wrasse! Wrasses are all born as females; environmental cues trigger some to become male. When a male Mardi Gras wrasse reaches the "terminal male phase," he develops a veritable rainbow of colors, like the brightly colored beads, floats, and other trimmings of Mardi Gras. Other species have also been discovered in this sanctuary, though not all are as colorful. In 2001 a new mantis shrimp was identified and in 2005 six algal species were announced. A new squat lobster—a small deep-sea crustacean whose front legs are comically outsized to its body size—joined the species roster in 2014. A new species of black coral, which contrary to its species name resembles a light green fern, was discovered in the sanctuary in 2020, shortly before the decision was made to expand the sanctuary's boundaries to include 14 additional reefs and banks.

Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument has also racked up an impressive array of new species, including algae, coral, sponges, nudibranchs, tunicates, fishes, even a new bird species, Bryan's shearwater. Closely related but genetically distinct to the little shearwater, the black and white Bryan's shearwater was named in 2011 and is critically endangered. More than seventy new species of algae—called limu in Hawaiian—have been discovered; one of them bears the name Umbraulva kuaweuweu, which refers to Kū, the Hawaiian god of prosperity. A new golden-hued seahorse was discovered in 2015 and Basabe's butterflyfish was described in 2016, a spiffy little black-and-white fish with yellow-trimmed fins.

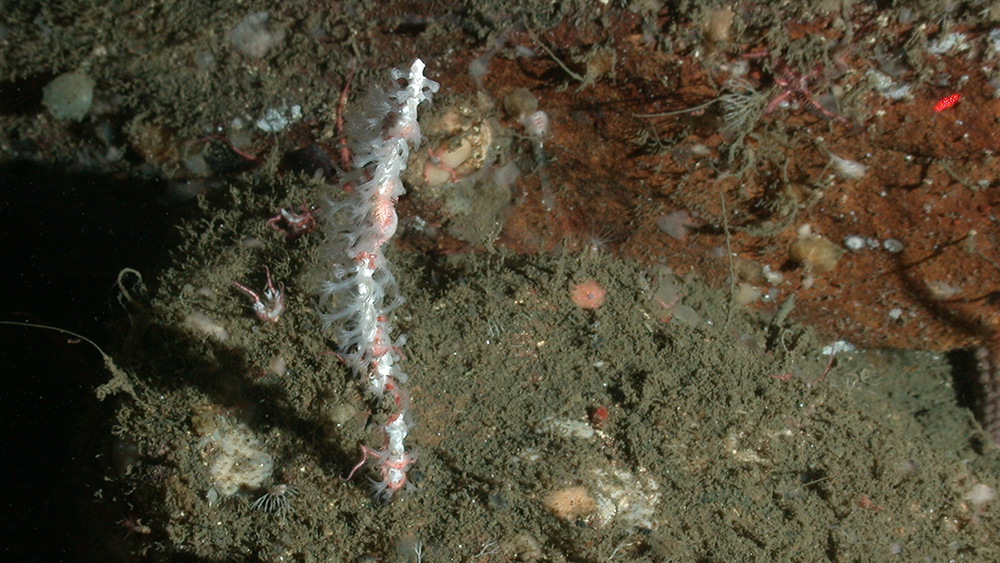

While some sites in the sanctuary system build their discovered species lists over decades, sometimes one or two expeditions will reveal a bonanza of new types of life. Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary led two research expeditions to Davidson Seamount in 2002 and 2006. Besides providing supporting evidence that helped make the case to expand the sanctuary to include the seamount, researchers also came away with fifteen new species, including eight sponges, three corals, and one each new ctenophore, nudibranch, polychaete, and tunicate. Two of the new sponges include "ruffled" in their names but don't really look alike; the stalked ruffled sponge resembles white blossoms on branches, while the ruffled sponge looks like a giant yellow brain. It only took four years of research with a remotely operated vehicle exploring the deepest parts of Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary but by 2008, seven new species of coral had been found, along with two new sponges and a nudibranch.

Over the years, other national marine sanctuaries have racked up new species discoveries of their own. Gray's Reef National Marine Sanctuary researchers found three new sea squirts in 2004 as they worked to build an invertebrate field guide for the sanctuary; two additional sea squirts were found in 2008. Scientists who discovered a new deep-sea coral species in Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary named it for the sanctuary in 2016: Swiftia farallonesica—a rather Dr. Suess-ian creature that is a tall, thin spike of white with little white trumpets growing from it.Cordell Bank logged a new coral species in 2019 that was also named for the sanctuary: Chromoplexaura cordellbankensis.

These are only a few of the hundreds of discovered species contributed by the sanctuary system to our shared "tree of life." But it isn't only new life that sanctuaries have found. We're also proud to have made discoveries that deepen our understanding of the nation's maritime heritage.

Understanding Our Maritime Heritage More Deeply

When a devastating oil spill hit the Santa Barbara Channel in 1969, it was frightening enough to prompt the nation's leaders to pass the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act that created the National Marine Sanctuary Program. But it was a shipwreck that led to the creation of the nation's first national marine sanctuary, that of the Civil War ironclad Monitor, found in 1973 off the coast of Cape Hatteras. Monitor National Marine Sanctuary kicked off what is now a distinguished maritime heritage research pedigree. Shipwrecks are only a part of that pedigree but the stories they tell continue to enthrall us.

One of the most tragic wrecks discovered by the sanctuary system is that of the steamship Portland, found in Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary in 2002. Nicknamed the Titanic of New England, Portland went down in a storm in 1898, taking the lives of all 193 people on board. ROV footage of the wreck shows unbroken white china cups and plates laying in piles in what had been the galley of the ship.

USS Conestoga, whose wreckage was found in 2014 in Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, tells a tragic story too, but one that resolved a mystery that had gone unanswered for nearly a century. In 1921, the vessel left Mare Island Naval Yard in California on its way to Pearl Harbor. But it never arrived and was officially declared lost with all 56 members of the crew on June 30, 1921. For years, the question troubled the U.S. Navy and the loved ones of the missing sailors: what had happened to Conestoga and its crew? Discovering the vessel's final resting place solved one of the nation's top maritime mysteries and gave resolution to the families of those who were lost.

Of all the wrecks discovered in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument—and there are over a dozen—Two Brothers, rediscovered by NOAA archaeologists in 2008, might be the most famous. Captained by George Pollard Jr., the vessel was the second whaler he had commanded. His previous whaler Essex was struck and sunk by a whale in the South Pacific, providing the inspiration for the novel Moby-Dick by Herman Melville. After the loss of Essex, Pollard and a handful of his crew resorted to cannibalism in order to survive during the 95 days they spent stranded in small boats in a vast ocean. Despite Pollard's notoriety after they were rescued and the story came to light, he was given Two Brothers. But misfortune stalked Pollard and Two Brothers struck a reef in French Frigate Shoals during a storm and sank. Pollard and his crew were forced to leave the vessel for small boats and the next morning were taken up by their sister whaler Martha; all were returned safely to Oahu.

Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary is a sanctuary of shipwrecks, over 200 known and suspected wrecks, each with a tale of loss to tell. One seemed unluckier than most, though. Chocktaw, a steel ship built in 1892 seemed to have a run of bad luck before its final bout with misfortune in 1915 when it sank after being hit by another ship off Presque Isle, including an engine explosion in 1893, a collision with another vessel in 1896, a grounding in 1900, and a partial sinking in 1902. The sanctuary discovered the wreck in 2017 during a summer research expedition, along with the wreck of Ohio, which sank in 1894 after colliding with another vessel.

Mallows Bay-Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary is also a shipwreck graveyard, in this case the remains of the World War 1-era ships of the "Ghost Fleet." These vessels tell the story of a nation preparing for not one but two world wars. Further south along the coast of North Carolina, sanctuary researchers have found numerous World War II wrecks, including U-boats 576 and 352, and the tankers Bluefields and Dixie Arrow, in waters adjacent to Monitor National Marine Sanctuary.

Taken together, these and all the found, suspected, and still undiscovered wrecks of the sanctuary system help build the story of our country's development as a modern maritime nation. But our history goes much deeper than that, thousands of years into the past, when the first humans arrived on the continent and found a bounty of natural resources that allowed them to roam, hunt, and fish, migrate and settle, and eventually develop cultures inextricably connected to lands and waters that give rise to the Native American tribes of today. And there too, sanctuary discoveries have a tale to tell.

Expanding the Knowledge of Our Deep History

Thousands of years ago, some of the areas we now call national marine sanctuaries were dry land: plains, wetlands, and forests, mountains and valleys, and long-drowned streams and rivers whose names, if they had any, have been lost. The edges of the sea were also much further offshore than today. As the last ice age ended, glaciers melted, freeing up seawater and flooding inland, transforming those vast landscapes into underwater habitats and pushing human and wildlife inhabitants further inshore. But the remains of human hunting and habitation can still be found even beneath the waves.

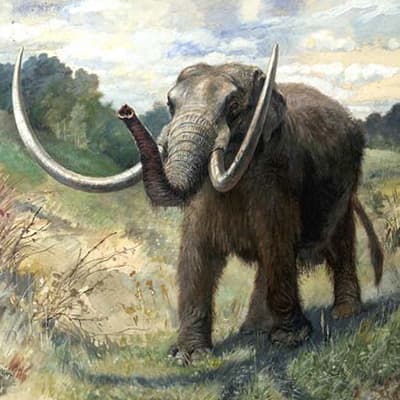

For example, in Gray's Reef National Marine Sanctuary, archaeologists have discovered drowned campfires and projectile points for arrows or spears; hunters might have once stalked wooly mammoths over what is now the seabed. Similarly, in the Thunder Bay area, archaeologists have found stone markers, obsidian projectile points, and rock hunting blinds used by hunters on ridgelines now drowned when the waters that are now Lake Huron rose with the end of the ice age. A 2006 excavation of a relic beach about two miles from the modern shoreline near Neah Bay, beside Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary, revealed that it was once a village besides an estuary, where ancient Makah hunters and fishers would have taken advantage of the bounty of the productive habitat.

The bones and teeth of mastodons and mammoths have been recovered by fishing gear from what is now Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary; imagine the bank as perhaps a forested hill patiently climbed by these gigantic tusked relations to today's elephants in search of breakfast among the trees, shrubs, and grasses. Archaeologists in the Florida Keys have uncovered remnants of a once extensive ancient pine forest buried in the waves off Key West; perhaps the ancestors of today's endangered key deer wandered among its trees. The oldest human remains discovered in the Americas, at least so far, are bone fragments dated to about 13,000 years ago on what is now Santa Rosa Island in Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary; one of the original Chumash names for the island is Wima, meaning driftwood, perhaps for the presence of driftwood that was used to build the traditional planked canoes called tomols.

Some of the discovered fossils also tell us the story of national marine sanctuaries as ocean places. In 2006, from a reef near Gray's Reef National Marine Sanctuary, marine archaeologists found the 36,000-years-old vertebrae and lower left mandible of the extinct Atlantic gray whale. Once both the north Atlantic right whale and the Atlantic gray whale were common in the waters of the southeastern US, but both, as nearshore, slow-moving species, were targeted by whalers in the 1600s and 1700s. Today the right whale is one of the most critically endangered marine mammals in the world; the Atlantic gray whale was not even that lucky, being decimated by whaling and considered extinct by about 1740.

Catching a Falling Star

Perhaps the most unusual discovery we've made in sanctuaries is the pieces of meteorite found in Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary in 2018. In March of that year, a meteorite broke up the planet's atmosphere and fell into the ocean inside the sanctuary's boundaries; experts were immediately interested in seeing if any of the meteorite fragments could be found, because they contain clues to the formation of our universe and help us understand how it came to be. By summer, the sanctuary had teamed up with NASA and other partners to conduct two research expeditions to recover fragments of the meteor. After locating its debris field, scientists used a specially designed magnetic rake to separate the meteor fragments from other material on the seabed. The fragments were collected and are being analyzed by NASA, the Smithsonian, and other experts.

A colorful new fish, the remains of a tragic ship, the bones of ancient elephants, the fragments of stars: these are some of the discoveries of the sanctuary system. These have all been opportunities to invoke wonder, to enjoy the combination of surprise and curiosity that is so important to our species. They have also been due to the scientific endeavors of sanctuary researchers and their partners, an effort that has been important for fifty years and will be even more important in meeting the challenges of the coming years.

It's been said that we know more about the moon than we do about our own ocean here on our homeworld. We don't know if that's true, but we do know that most—80% by some estimates—of the ocean remains essentially unexplored and unmapped. That means many more things oceanic await our discovery—and many more chances to say, "wow!"